American Conservatory ...,

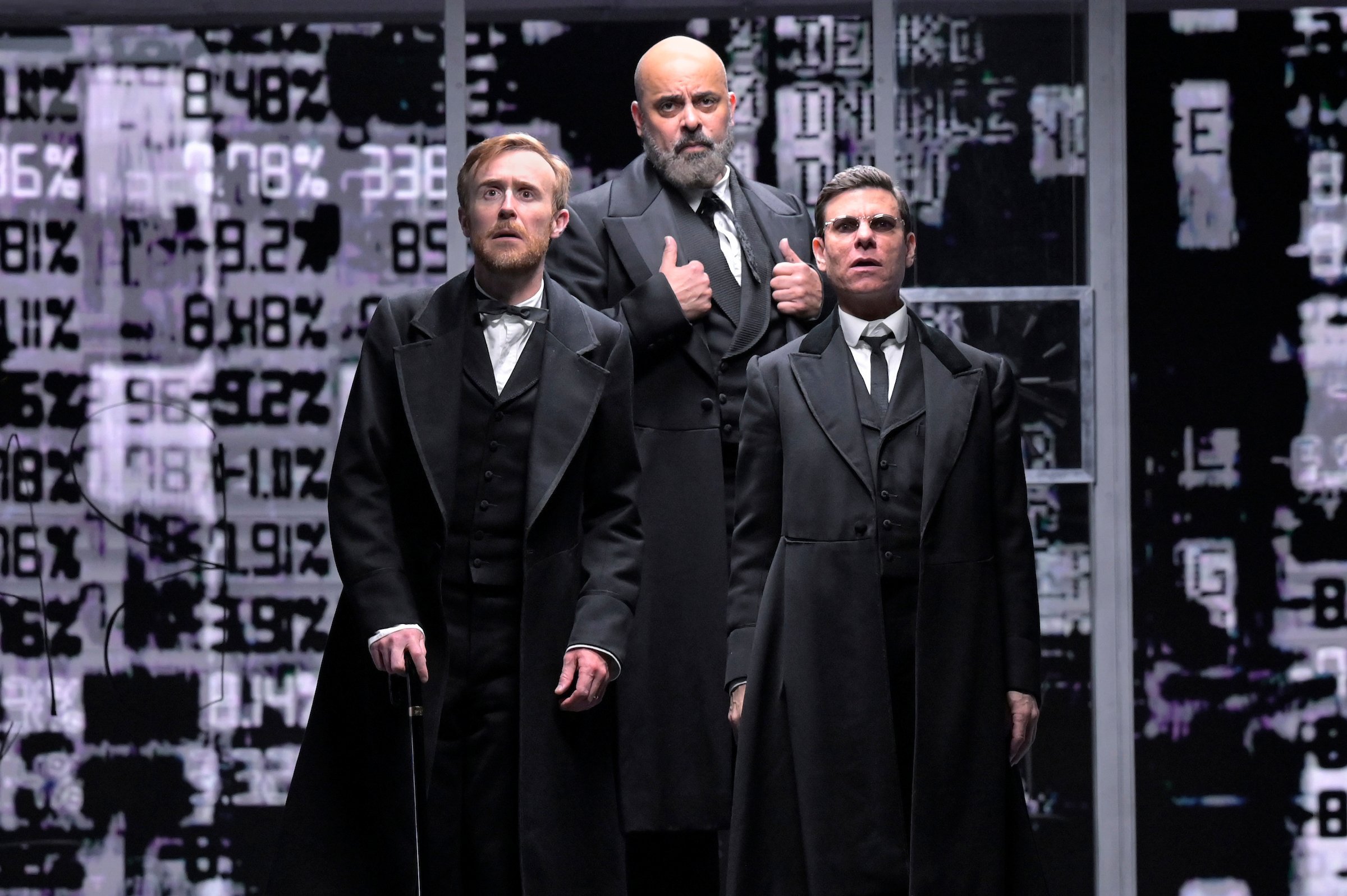

sam mendes,

The National Theatre,

Es Devlin,

Stefano Massini,

Ben Power,

theater review,

plays

Chad Jones

American Conservatory ...,

sam mendes,

The National Theatre,

Es Devlin,

Stefano Massini,

Ben Power,

theater review,

plays

Chad Jones

Read More

American Conservatory ...,

BD Wong,

Jomar Tagatac,

Kate Attwell,

Michael Phillis,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

theater review,

World premiere

American Conservatory ...,

BD Wong,

Jomar Tagatac,

Kate Attwell,

Michael Phillis,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

theater review,

World premiere

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Dan Hiatt,

Leslye Headland,

local theater,

plays,

theater review,

Trip Cullman

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Dan Hiatt,

Leslye Headland,

local theater,

plays,

theater review,

Trip Cullman

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Eisa Davis,

Jordan Tyson,

Nicole A- Watson,

plays,

theater review

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Eisa Davis,

Jordan Tyson,

Nicole A- Watson,

plays,

theater review

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Jack Thorne,

John Tiffany,

National Theatre of Sc...,

plays,

Steven Hoggett,

theater review

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Jack Thorne,

John Tiffany,

National Theatre of Sc...,

plays,

Steven Hoggett,

theater review

Read More

Annie Smart,

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Mina Morita,

plays,

Sanaz Toossi,

theater review

Annie Smart,

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Mina Morita,

plays,

Sanaz Toossi,

theater review

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Chay Yew,

Dengue Fever,

Francis Jue,

Lauren Yee,

musicals,

plays,

theater news

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Chay Yew,

Dengue Fever,

Francis Jue,

Lauren Yee,

musicals,

plays,

theater news

Read More

American Conservatory ...,

Christopher Chen,

local theater,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

theater review

American Conservatory ...,

Christopher Chen,

local theater,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

theater review

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Huntington Theatre Com...,

local theater,

Lynn Nottage,

plays,

Taylor Reynolds,

theater review

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Huntington Theatre Com...,

local theater,

Lynn Nottage,

plays,

Taylor Reynolds,

theater review

Read More

Brian Copeland,

David Ford,

plays,

The Marsh,

theater review,

World premiere

Brian Copeland,

David Ford,

plays,

The Marsh,

theater review,

World premiere

Read More

Aaron Sorkin,

Bartlett Sher,

BroadwaySF,

plays,

Richard Thomas,

theater review

Aaron Sorkin,

Bartlett Sher,

BroadwaySF,

plays,

Richard Thomas,

theater review

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Christina Anderson,

Goodman Theatre,

Jackson Gay,

plays,

theater review,

World premiere

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Christina Anderson,

Goodman Theatre,

Jackson Gay,

plays,

theater review,

World premiere

Read More

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Les Waters,

local theater,

Lucas Hnath,

plays,

theater review,

Tony Awards

Berkeley Repertory The...,

Les Waters,

local theater,

Lucas Hnath,

plays,

theater review,

Tony Awards

Read More

American Conservatory ...,

Catherine Castellanos,

Cindy Goldfield,

Lisa Anne Porter,

local theater,

Marga Gomez,

María Irene Fornés,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

Stacy Ross,

theater news,

theater review

American Conservatory ...,

Catherine Castellanos,

Cindy Goldfield,

Lisa Anne Porter,

local theater,

Marga Gomez,

María Irene Fornés,

Pam MacKinnon,

plays,

Stacy Ross,

theater news,

theater review

Read More

Curran Theatre,

Harry Potter,

J-K- Rowling,

Jack Thorne,

John Tiffany,

plays,

Steven Hoggett,

theater news,

theater review

Curran Theatre,

Harry Potter,

J-K- Rowling,

Jack Thorne,

John Tiffany,

plays,

Steven Hoggett,

theater news,

theater review

Read More

Adam Magill,

Fumiko Bielefeldt,

Lauren Gunderson,

Lauren Spencer,

Margot Melcon,

Marin Theatre Company,

Meredith McDonough,

Nina Ball,

plays,

theater news,

theater review,

World premiere

Adam Magill,

Fumiko Bielefeldt,

Lauren Gunderson,

Lauren Spencer,

Margot Melcon,

Marin Theatre Company,

Meredith McDonough,

Nina Ball,

plays,

theater news,

theater review,

World premiere

Read More