Facing a fearsome farce in Berkeley Rep'sOctoroon

ABOVE: Lance Gardner is George, a new plantation owner, in the West Coast premiere of An Octoroon by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins at Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

BELOW: Afi Bijou (left) is Minnie and Jasmine Bracey is Dido, slaves on the Terrebonne Plantation. Photos courtesy of Kevin Berne/Berkeley Repertory Theatre

What a miserable species we are.

Existence is difficult enough as it is, but we compound the misery with our unrelenting egomania, greed and all the isms and phobias and ogenies. We unleash a never-ending torrent of cruelty in the name of power and money thinking it will somehow fix something, be it global or deeply personal, and yet it always ends in a big pile of bloody pulp or crap or both. In the big picture, we don't ever seem to learn. But in the smaller picture, we're at least getting a little smarter.

Artists like Branden Jacobs-Jenkins do that cracked-mirror thing that helps us see where we've been and where we are. None of it is pretty, but his wild play An Octoroon, now at Berkeley Repertory Theatre's Peet's Theatre grabs you by your painful parts and delivers a surprising, funny and provocative 2 1/2 hours of theater.

To call this simply a play isn't really accurate. An Octoroon is a meta-theatrical fantasia, layers upon layers of art and history, comedy and tragedy, music and melodrama, abrasive satire and inspired clowning. This experience is never just one thing, and that could be an unwieldy thing, but director Eric Ting, the artistic director at the California Shakespeare Theater, has a firm grasp of the constantly shifting situation.

To begin with, this is an adaptation of an adaptation. Jacobs-Jenkins is adapting Dion Boucicault's 1859 hit The Octoroon, which is itself adapted from a then-contemporary novel, The Quadroon by Thomas Mayne Reed. The antebellum-era plot involves a faltering plantation, the sale of its slaves and a love story between a slave owner and a woman who is part black (one-eighth is an octoroon, a terrible word if ever there was one; one-quarter is a quadroon, just as terrible).

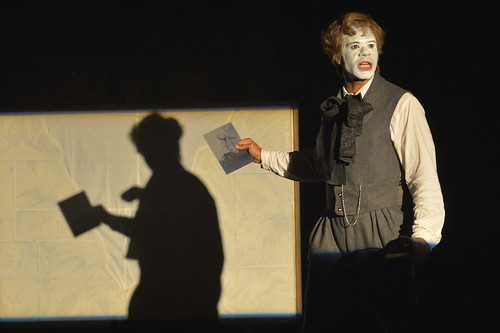

All of that is still here, performed in a style between melodrama and farce (all accompanied on a jangly piano by Lisa Quoresimo in a Br'er Rabbit costume), but Jenkins gives us a very contemporary frame with a playwright character named BJJ (played by the always appealing Lance Gardner) who is working through his own personal issues (what does "black playwright" mean anyway?) taking the advice of a therapist he may or may not have by adapting the Boucicault play. Problem is that his white actors hired to play the slave owners have quit, so he slaps on some whiteface and plays the characters himself. Another writer appears, known simply as "Playwright." This one is a stand-in for Boucicault himself and is played by Ray Porter, a ferocious presence on stage. Boucicault will also be in BJJ's play. He's playing the Native American character Wahnotee, and by the logic of this world, he naturally paints his face red for the role and dons an enormous feathered headdress (think Bob Mackie and Cher – fantastically stylish costumes by Montana Blanco). He'll also play a slave trader, and BJJ will take on another role as well: the mustache-twirling villain who wants to sink the plantation and sell off Zoe (Sydney Morton), the octoroon, who is already in love with George, the plantation owner played by BJJ in whiteface.

The slave women in the play, primarily Dido (Jasmine Bracey) and Minnie (Afi Bijou), work in the house and are fairly straightforward, but rather than seeming like they're in a 19th-century melodrama, they discourse like two women who have their own podcast about what's going down on the old plantation. They're hilarious and trenchant, and the weariness of the melodrama is enlivened whenever they're on stage.

Because the law forbids the love between George and Zoe, George must attempt to make a profitable union in an effort to save his plantation. He turns to plantation neighbor Dora, played by Jennifer Regan in full-on goofy Carol Burnett mode (always a good thing, especially when stylistically appropriate, as it is here). And the world of the plantation is further filled out by Afua Busia as Grace, a pregnant slave (who also has a baby with a face that has to be seen to be believed) and Amir Talai, a non-Caucasian actor in blackface playing two slaves, including one whose name features the n-word. Speaking of that word, you hear it a lot, so however you need to deal with that, there it is.

The play is at its strongest when it's not simply presenting the adaptation of Boucicault but is messing with it – and us. That means the best bits are at the beginning of the play and then in Act 2 when the melodrama becomes too outrageous to continue with a small cast (and not enough mean white men). Jacobs-Jenkins attempts to rattle a modern audience the way a 19th-century audience might have been rattled by certain twists in the plot. Let's just say he pulls out some heavy artillery for this mission, and set designer Arnulfo Maldonado, with a huge assist from Jiyoun Chang's effective lights, offers yet another design surprise to wrap things up with yet another tonal shift.

The ending brings us back to now, but in a timeless way (voices joined), but there's little sense of resolution. How could there be? The Boucicault melodrama traffics, as all good melodrama does, in abject misery created by societal restrictions, and choosing the American South for such an exploration is rife with the kind of misery that has created every kind of drama every minute of every year since. In a theatrical experience like this, we see the mess. We laugh at it, we flinch from it, we bristle.

Some will likely take offense at the whiteface, the blackface or the redface or the n-word or the drinking of an entire bottle of wine in one go or the inclusion of a mammy or a stage overrun with cotton balls or an actor playing two characters attempting to murder himself (Gardner is a deft physical comedian) or the sight of a man giving himself a wedgie. But there's no denying how effective An Octoroon is at not letting anyone off the hook. This is our mess, our misery, our melodrama, our tragedy, our farce. That Jacobs-Jenkins and the entire on-stage and off-stage crew of An Octoroon have made it so powerful, so baffling and so, dare I say it, so entertaining, is nothing short of a modern theatrical wonder.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins' An Octoroon continues an extended run through July 29 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre's Peets Theatre, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $29-$97 (subject to change). Call 510-647-2949 or visit berkeleyrep.org.