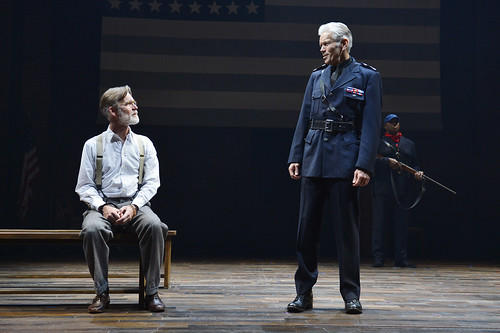

Tony Award-winner Ari’el Stachel stars in the world premiere of his autobiographical solo show Out of Character at Berkeley Rep. Photo by Kevin Berne/Berkeley Rep

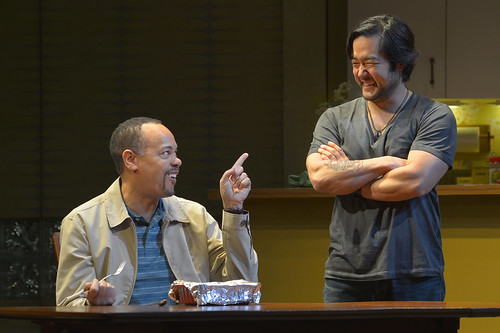

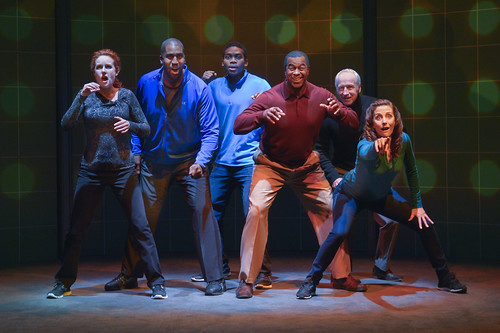

As a performer, Ari’el Stachel is everything you want on stage, especially in a solo show. He’s charming, dynamic, kinetic and fabulously entertaining. In his world-premiere autobiographical one-man show Out of Character, now on stage at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Peet’s Theatre, he plays more than three dozen characters, does a little singing (sublime beyond sublime), a little dancing (perhaps not so sublime, which is why he got into singing) and a whole lot of exploration into two things that have played major roles in his 30-plus years on the planet: identity and anxiety.

Directed by Tony Taccone, Berkeley Rep’s former artistic director and something of an expert in solo shows (see Sarah Jones, Carrie Fisher, Danny Hoch, Rita Moreno, John Leguizamo), Character comes out of Berkeley Rep’s Ground Floor new works development program and still feels, frankly, like a new work. That said the production is superb, with a striking stage design by Afsoon Pajoufar whose shapes and textures are beautifully augmented by the lights and projections from Alexander V. Nichols.

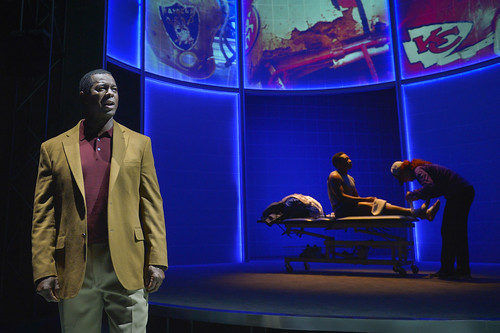

The 80-minute show begins with what should be a high point in the life and career of Berkeley native Stachel: the night in 2018 when he won the Tony Award for best featured actor in a musical for his role in The Band’s Visit. But that night, as we see, only exacerbated his lifelong struggle with anxiety, and he ended up spending time hiding out in the bathroom rather than being celebrated for his triumph.

Diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder as a kid, Stachel struggled in numerous ways – first with the voice in his head, which he named Meredith after the scheming girlfriend in the 1998 remake of The Parent Trap, and second with his growing shame connected to his Yemeni-Israeli-Ashkenazy Jew roots. After 9/11 (when he was 10), life got even more complicated – especially at school – for a brown boy whose bearded dad got immediately branded “Osama” by the other kids.

So the intertwined narrative of Stachel’s show is the anxiety, which often results in abundant, visible sweating, and the ways he would slip into identities to protect himself from his outer and inner worlds. At Berkeley High, for instance, he passes for black, and he’s thrilled that he can finally be “cool.” But then in college, he finally embraces his Middle Eastern heritage, until that too seems like a character he’s playing. And everywhere along the way, there’s Meredith (realized in the excellent sound design by Madeleine Oldham) promising the end of the world if he doesn’t do exactly as she says.

What it is to be American emerges as a fascinating aspect of the show, especially when Stachel is on vacation in Kampala, Uganada, and is seen as just another white guy. But here, as with the examination of anxiety, Stachel’s writing doesn’t yet match his strength as a performer. The way he tries to make peace with Meredith internally and with his father externally aren’t yet fully realized, and the show doesn’t feel finished by its conclusion. Perhaps that’s because Stachel is still so actively living his experience and figuring out the day to day. There are more depths to plumb here, but Stachel should rest assured that he’ll never find a more charismatic actor to enliven his evolving script.

[bonus video]

Ari’el Stachel performs “Haled’s Song About Love” from The Band’s Visit (2018)

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Ari’el Stachel’s Out of Character continues through July 30 at Berkeley Repertory Theater’s Peet’s Theatre, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Running time: 80 minutes (no intermission). Tickets are $39-$119 (subject to change). Call 510-647-2949 or visit berkeleyrep.org.