Sarah Nina Hayon and Sean San José star in the world premiere of Octavio Solis’ Se Llama Cristina at Magic Theatre. Below: Rod Gnapp is the embodiment of bad guys plaguing the lives of struggling people. Photos by Jennifer Reiley

There are moments when Octavio Solis’ darkly poetic writing leaves me breathless. Take this passage from his world-premiere play Se Llama Cristina as two lovers are driving down a lonely highway. The driver looks at his sleeping passenger and says: “And your head is leanin’ against the window and the passing cars light up your face like a Hollywood starlet. Famous, then not. Famous, then not.”

Truth be told, there are also moments when the San Francisco playwright’s writing leaves me befuddled, and that happens, too, in Se Llama Cristina. But confusion and mystery is part of the foundation – albeit rocky a rocky one – on which this intriguing drama is built.

Essentially Solis is telling the story of everyday triumph, specifically the ability move beyond the horrors of the past to stake a claim as a functioning – however flawed – human being capable of sustaining important relationships such as spouse to spouse or parent to child. Parenting is the guttering neon sign at the center of this creation, flickering at various levels of brightness until it all but explodes by the end.

Solis eschews a linear narrative and, curiously, turns his protagonists into audience members as they watch their story unfold in bits and pieces, with flashbacks within flashbacks and even flash-forwards.

Lights come up on a dingy, battered room (the low-ceilinged set is by Andrew Boyce). A man and a woman are just coming to after what appears to have been quite a bender. The guy still has the rubber strap tied around his arm with a syringe embedded in his skin.

Neither of these characters knows their names, where they are or how they came to be so drugged up. The doors and windows of the room are locked, and there’s a crib in the corner. Only instead of a baby, the crib holds a piece of fried chicken, a drumstick.

We’re just as confused as the characters on stage, and when the first explanatory flashback happens, we learn things right along with them. How that works exactly, I’m not sure. I know how it works for the audience, but what exactly are the characters seeing in that room? That’s really too literal a question for this play, which has the feeling of a fever dream leading up to the making of a pivotal life decision.

Director Loretta Greco’s production feels substantial, even at only 85 minutes. As the play jerks us back and forth in time and tone – flights of poetry crash against gritty realism – she guides her cast from a strong emotionally grounded center.

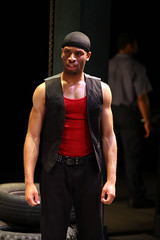

Sean San José and Sarah Nina Hayon are superb as broken people who don’t expect to accomplish much in this life beyond surviving and making mistakes. They find each other by accident and begin a journey, sometimes a reluctant one, toward realizing potential they didn’t know they had. As rough and gritty as this play is, there’s a current of hope that continually pushes through the violence and neglect and poverty (of many kinds) in these people’s lives.

San José, whose character is a would-be poet, is especially adept at navigating Solis’ dramatic turns from naturalism to fantasy. He has two scenes on the phone, one with Hayon and one with a figure from his past, and both are incredible. One of those conversations is mostly in Spanish, and you don’t have to understand a word of the language to feel your heart break along with the character.

If you want charm and menace in equal measure, Rod Gnapp is your go-to guy. Here he embodies every bad choice a woman can make, and though he’s a walking nightmare (an effect augmented by Sara Huddleston’s sly sound design), he’s also funny as hell and completely recognizable as someone you may know.

The performances are so good here (the cast also includes a nice turn by Karina Gutiérrez) that they almost compensate for the ways in which the fractured structure confuse the narrative and cloud the emotional impact. Piecing it all together isn’t all that hard, but the emotional through line gets somewhat clouded because there are so many questions about what is reality and what isn’t. Questions are good in drama, but when those questions are straddling dream and reality, it’s hard to know what to trust and grab hold of so that by the end you’re holding on to what’s important in this story.

But then again, that’s so much of what Se Llama Cristina is about: what’s worth holding onto and what’s better left behind. Sometimes you don’t have a choice in that, but sometimes you do.

[bonus interviews]

I talked to director Loretta Greco and playwright Octavio Solis for a feature in the San Francisco Chronicle. Read the story here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Octavio Solis’ Se Llama Cristina continues through Feb. 5 at Magic Theatre, Building D, Fort Mason Center, Marina Boulevard at Buchanan Street, San Francisco. Tickets are $22-$62. Call 415-441-8822 or visit www.magictheatre.org.

And one of the recipients was Berkeley-based California Shakespeare Theater, which will spend 20 grand on early play development activities — read-throughs, public readings and workshop productions — for Pastures of Heaven, which is being written by San Francisco’s Octavio Solis (right), based on a collection of interlinking short stories by John Steinbeck. The piece is being developed with San Francisco’s Word for Word Performing Arts Company.

And one of the recipients was Berkeley-based California Shakespeare Theater, which will spend 20 grand on early play development activities — read-throughs, public readings and workshop productions — for Pastures of Heaven, which is being written by San Francisco’s Octavio Solis (right), based on a collection of interlinking short stories by John Steinbeck. The piece is being developed with San Francisco’s Word for Word Performing Arts Company.

Eleven top regional theatre actors from around the country have been selected as the inaugural

Eleven top regional theatre actors from around the country have been selected as the inaugural