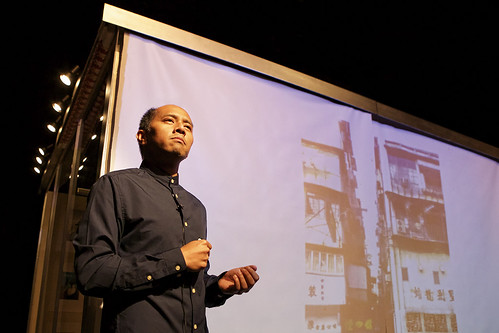

The cast of the world-premiere Georgiana and Kitty: Christmas at Pemberley includes (from left) Lauren Spencer as Georgiana Darcy, Aidaa Peerzada as Emily Grey, Emilie Whelan as Kitty Bennet, Zahan F. Mehta as Henry Grey, Adam Magill as Thomas O’Brien, Alicia M. P. Nelson as Margaret O’Brien and Madeline Rouverol as Sarah Darcy. Below: Mehta and Spencer find holiday romance in the Marin Theatre Company production. Costumes by Fumiko Bielefeldt, Scenic Design by Nina Ball, Lighting Design by Wen-Ling Liao. Photos by Kevin Berne courtesy of Marin Theatre Company

Jane Austen has undoubtedly been visiting with her celestial publisher to check on the status of her earthly estate. Over the years, she has seen her cultural clout grow and grow, with movies, novel sequels, themed weekends and generation after generation of new Austen fans clamoring for more. Among the most interesting of the offerings related to the much-loved 19th-century novelist created in the more than 200 years since her death are the Christmas at Pemberley plays by San Francisco playwrights Lauren M. Gunderson and Margot Melcon.

Locally, we saw the post-Pride and Prejudice Christmas at Pemberley series begin in 2016 at Marin Theatre Company with Miss Bennett (read my review marintheatre.org) and continue in 2018 with The Wickhams (a sort of below-stairs/Downton Abbey take). Now, what has become a trilogy, concludes with Georgiana and Kitty. The genius of the trilogy is that it essentially covers one Christmas holiday but doesn’t actually require you to have seen the other installments (or read Austen, for that matter) – but your enjoyment and appreciation will be enhanced if you have.

This third chapter is the most audacious of them all if only because it takes the greatest liberties with Austen by imagining what the five Bennett sisters, their husbands and children will be doing 20 years after this initial holiday gathering. Not to give anything away, but the future for these characters involves bold moves for womankind, enduing female friendship and consistent breaking of women’s societal restraints – all within a warm holiday glow and amid boisterous (sometimes contentious) familial affection.

We didn’t actually get to meet Kitty Bennett in either of the other two plays, so it’s lovely to see the youngest Bennett finally get her moment in the spotlight along with her BFF, Georgiana Darcy, sister of Fitzwilliam Darcy, husband of Kitty’s sister Lizzy.

There’s great excitement in the house because of – what else? – boys. Georgiana (Lauren Spencer) has been corresponding with Henry Grey (Zahan F. Mehta), a potential beau, for almost a year, and she has impulsively invited him to visit Pemberley at Christmas. He arrives, smitten and tongue-tied, in the company of his friend Thomas O’Brien (Adam Magill), who immediately sparks with the vibrant Kitty (Emilie Whelan). But this double romance quickly skids to a halt when Henry fails to pass muster with Georgiana’s domineering brother, Darcy (Daniel Duque-Estrada), whose self-imposed duty to protect his sister makes him overbearing and obnoxious.

The great thing about all the Pemberley plays is how they play with formula – calculated through both Austen and holiday romance equations – and still come up with something that is highly enjoyable, smart and full of real charm and warmth. Gunderson and Melcon honor Austen and write characters who defy expectations of the 19th, 20th and 21st century varieties. The holiday aspect wouldn’t be out of place in a Hallmark movie, but there’s an intelligence and spirit at work here that far exceeds all the usual, sappy trappings.

Performances are bright and focused in director Meredith McDonough (who also helmed Miss Bennett five years ago), and if some of the characters seem to be extra set dressing (on Nina Ball’s stately estate set), that is rectified when the action shifts ahead two decades and we meet a vivacious new generation of Darcys, O’Briens and Greys.

Austen would no doubt love to see the triumph of some her women characters as envisioned by Gunderson and Melcon, whether it’s the successful balancing of family and work life by one or the artistic success of another as she makes great inroads in a world wholly dominated by men. She may also love that even in the future, Mr. Darcy is a well-meaning ass who would do well to listen to his wife, who is seldom, if ever, wrong.

It’s a little bit sad that Kitty and Georgiana is the final chapter in the Christmas at Pemberley trilogy, but here’s hoping that Gunderson and Melcon continue to make such savvy, satisfying theater.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Georgiana and Kitty: Christmas at Pemberley continues through Dec. 19 at Marin Theatre Company, 397 Miller Ave., Mill Valley. Tickets are $25-$60. Call 415-388-5208 or visit marintheatre.org.