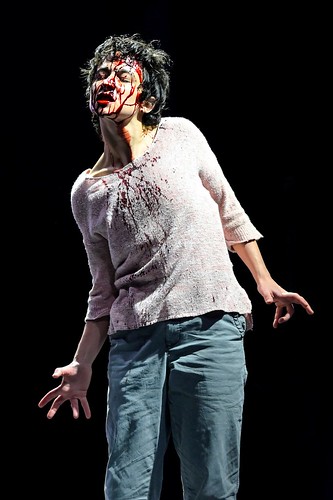

ABOVE: Noah Lamanna is Eli in the West Coast premiere of the National Theatre of Scotland production of Let the Right One In. BELOW: Diego Lucano (left) as Oskar and Lamanna as Eli. Photos by Kevin Berne

Let the right one in

Let the old dreams die

Let the wrong ones go

They do not

They do not

They do not see what you want them to

– Morrissey, “Let the Right One Slip In,” 1992

Horror on stage is a tricky, bloody business. I can only think of maybe twice when I have been truly chilled in my theater seat, and one of them came from the team behind Let the Right One In now on stage at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Roda Theatre, though not in this show. Writer Jack Thorne, movement director Steven Hoggett and director John Tiffany were also involved with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, which achieves some gleefully chilling moments involving Dementors and time warps.

But their work on Let the Right One In, an adolescent love story involving vampires and bullies, pre-dates that (and their work on the altogether warmer and more musical stage adaptation of Once). This show, which is based on the 2008 Swedish movie and 2004 novel of the same name (both written by John Ajvide Lindqvist), debuted at the National Theatre of Scotland in 2013 and has since played London and New York. Now, with an American cast, the show makes its West Coast premiere with a chilly, chilling production in Berkeley.

It’s not exactly scary, but it is utterly compelling, and the frozen beauty of the original film has been realized theatrically with a spectacular winter forest (set design by Christine Jones) that seems to be in the perpetual blue night of the late Chahine Yavroyan’s shadowy lighting design.

Specifically, it’s the ’80s in a Stockholm suburb on stage, but really it’s the desolate wilderness of adolescence that we’re witnessing. Oskar (Diego Lucano) is bullied to the point of physical injury at school and tormented at home by an often drunk mother and a father who lives elsewhere with other concerns. After a particularly brutal day at school, Oskar is in the woods outside his apartment complex sparring with trees and imagining himself to be the world’s greatest knife fighter. That’s when he meets Eli (Noah Lamanna), who has recently moved into the complex accompanied by a parent? a guardian? a guy whom we’ve just seen stringing up some poor lug in the woods and slitting his throat?

Perpetually alone and isolated in his misery, Oskar sparks to the notion of a friend, even a weird one that smells like wet dog or infected bandage. But the worldly Eli is quick to state that they will not be friends, though the rules of storytelling – horror story, love story or otherwise – dictate that their loneliness will join them and alter their lives.

What is never stated explicitly here is that Oskar is 12 and Eli is a 200+ year-old vampire (a world you will not hear in the show’s two-plus hours). But we get it. Thorne’s script is spare on details but long on mood (and, thanks largely to the wonderfully youthful Locano, winsome humor). Act 1 really sets the mood, makes the connections and sets the plot in motion. Act 2 picks up speed and conjures up some wild imagery (the superb special effects are designed by Jeremy Chernick) all the while underscoring that while this human-scale monster tale is really a coming-of-age story that blossoms (thornily) into a love story.

There’s a fair amount of blood, naturally, but Tiffany and Hoggett are more interested in the emotions here. We get a sense of the town through the constant shuffle of people through the woods (though there are only nine actors in the cast) and various interludes of dance that sometimes feel natural and sometimes kind of silly. The adults tend to overact and overreact, so the heart of the story easily becomes Oskar and Eli and the fantastic performances by Lucano and Lamanna as they convey the awkwardness and intensity of young love. Even though one is 12 and one has been alive since the 18th century.

There are echoes of Stephen King’s Carrie here with the potent cocktail of teen angst (or tween, to be exact), aggressive bullying, encounter with the supernatural and revenge tragedy (at one point Oskar is reading a book that looked like a King novel, but my eyes couldn’t be certain). The details are different, of course, but there’s that universal recognition of the horror that is high school, the torture of rejection by the mainstream and finding the power to make your own way. It’s not exactly a happy ending, but the right ones do find one another, and the wrong ones do go away.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

The National Theatre of Scotland’s Let the Right One In continues through June 25 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Roda Theatre, 2015 Addison St., Berkeley. Running time is 2 plus a 15-minute intermission. Tickets are $43-$119 (subject to change). Call 510-647-2949 or visit berkeleyrep.org.