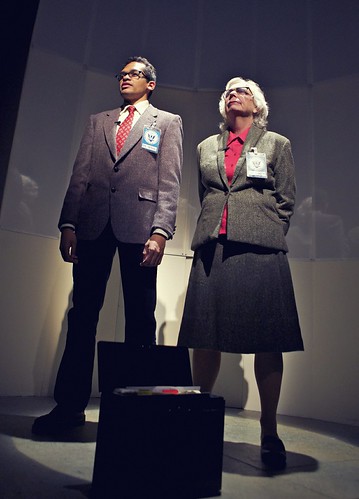

ABOVE: The cast of Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s English includes (from left) Sarah Nina Hayon as Roya, Christine Mirzayan as Goli and Mehry Eslaminia as Elham. BELOW: Sahar Bibiyan is Marjan, the instructor, and Amir Malaklou is Omid, one of her best students. Photos by Alessandra Mello

It’s so interesting that in Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s English, your ears have to become accustomed to hearing English. Playwright Sanaz Toossi’s sensitive comedy/drama is set entirely in a classroom in Karaj, Iran circa 2008. The instructor and her four students are engaged in English lessons leading up to the exam known as the TOEFL or Test of English as a Foreign Language. The play is (almost) entirely in English, so when the characters are speaking their native Farsi, they speak in unaccented, colloquial English. When they are communicating in English, we hear varying degrees of accents and grammatical skills, depending on the level of the speaker.

It’s a clever way to fall into the cadence of toggling between two languages without having to use sub/surtitles. There’s more engagement with the characters and their various states of mind, and it’s fascinating to contrast the levels of confidence some of the characters display when speaking their own language compared to the personality transformation that can happen when they are attempting to speak in a language that is not coming easily to them.

Director Mina Morita lets this one-act play unfold slowly as we get to know Marjan (Sahar Bibiyan), the instructor who lived, for a time, in England and still enjoys watching British rom-coms to keep her English skills sharp, and her small class. The biggest personality among them is Elham (Mehry Eslaminia), who has failed all past attempts at the TOEFL and struggles with everything about English. She’s under pressure to pass the exam because she’ll soon be starting medical school in Australia. Goli (Christine Mirzayan) is much more enthusiastic, and it’s one of the play’s many pleasures to see this youthful student gaining confidence in her language skills. Omid (Amir Malaklou) catches Marjan’s eye, and not just because he’s such a strong English speaker, and Roya (Sarah Nina Hayon) is, essentially, being forced to learn English by her son, who is now living in Canada and doesn’t want his child speaking Farsi with anyone.

In about two dozen scenes, we see the ups and downs of the students, perhaps a romance and some minor drama (speaking strictly in dramatic terms). But within these very recognizable rhythms are lives in motion and the push and pull of family, career, culture, politics. We’re only seeing these people across six weeks or so and only during their classes, so we experience slivers of their lives even while they are creating the community that can happen in a classroom (complete with bonds and battles).

What comes through so remarkably in this intimate, often quite hilarious play is how oblivious we can be to the importance of language in expressing our identity. The idea of belonging or being an outsider based on how you speak is explored, as is the joy of being able to express yourself in a new way or to make someone laugh in a different language. Can a new language be an escape? A salvation? A personal revolution? Or maybe even a shortcut to an appreciation of your own native tongue? Playwright Toossi keeps her scope narrow, but she allows the weight of the world to press in on this little group.

Morita’s wonderful cast works in shades of nuanced reality that allow us to feel like we’re really getting to know these characters. Even when Toossi’s script can be a little too placid, a little too subdued, there’s abundant warmth and humor that keeps us deeply invested in these people’s lives.

There’s always going to be something funny in someone mangling language – not in a jeering way but in appreciation of the bravery required to even make the attempt – and that is certainly a big part of the laughs in English, but even more, the humor bonds us. When we laugh together (in real life and in the theater) we’re acknowledging the depth of communication – our shared humanity, our empathy, our awareness. We may not all speak English, but in English, especially in those moments of comedy, we’re all speaking the same language.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Sanaz Toossi’s English continues through May 7 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Peet’s Theatre, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $43-119. Running time: 1 hour and 40 minutes (no intermission). Call 510-647-2949 or visit berkeleyrep.org.