EXTENDED THROUGH NOV. 5

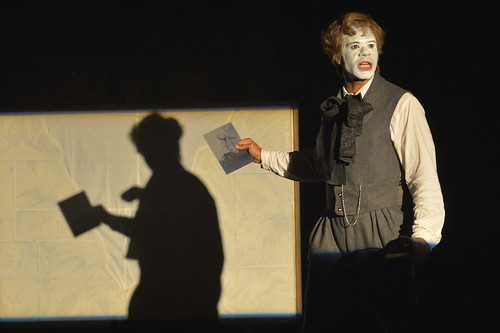

The cast of Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s world-premiere musical Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of The Temptations includes (from left) Christian Thompson as Smokey Robinson, Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin, Jared Joseph as Melvin Franklin, Derrick Baskin as Otis Williams, Jeremy Pope as Eddie Kendricks and James Harkness as Paul Williams. Below: The Temptations – (from left) Sykes, Pope, Harkness, Joseph and Baskin – show off their moves. Photos by Carole Litwin/Berkeley Repertory Theatre

When Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of The Temptations is in its groove, this world-premiere musical at Berkeley Repertory Theatre is absolutely electrifying. Featuring all or part of 30 songs from the ’60s and ’70s Motown era, the music alone is enough to make this a must-see theatrical event, but it’s clear that this musical biography is going places (namely Broadway).

It’s not surprising that the story of The Temptations, one of the most successful R&B groups in pop music history, is being given the stage musical treatment. Perhaps what’s surprising about this venture is that it involves two of the major talents behind another, incredibly successful stage bio: Jersey Boys. Director Des McAnuff and choreographer Sergio Trujillo return for another chapter of pop music history translated to the musical theater stage, and the results are similarly thrilling and tuneful. Here’s another story about a scrappy boy band that hits it big, suffers the usual success-related plagues (ego, drugs) and survives with the music (if not the original band members) prevailing. Think Jersey Boys meets Dream Girls to create Detroit Dream Boys.

What’s interesting about Ain’t Too Proud is that it begins in Detroit, with the eventual formation of the five-member band and its eventual acceptance into the stable of resident hitmaker Berry Gordy and his Motown label. After struggling to get traction on the charts, the Temptations finally break through with “The Way You Do the Things You Do,” and by the late ’60s and early ’70s, they’re struggling along with most of the country to adapt to rapidly changing times and tastes all the while dealing with some explosive personalities within the band, which leads to a sort of revolving door of members of the remainder of its existence. We’re told that from 1963 to the present day (there is still a band called The Temptations making music in the world), two dozen men have been in (and out) of the band. That’s a lot of guys to keep track of in a musical biography, so book writer Dominique Morisseau (a noted playwright and Detroit native) focuses primarily on the original five members for the first act and the first few replacements in the second act, which can’t help but lose some of its focus as years and members seem to speed by without much specificity.

The musical is based on the book The Temptations by founding member Otis Williams – the same book that served as a basis for the two-part 1998 NBC miniseries “The Temptations – so the story is told primarily from his point of view. As played by the charismatic and eminently likable Derrick Baskin, Otis is savvy and hardworking, a team player who makes up in reliable good nature what he may lack in showbiz pizzazz. He’s the through-line of the story, serving as its narrator and amiable main character (and at Thursday’s opening-night performance, the real Otis was in the theater beaming at his on-stage alter-ego).

A single song, like “Shout” can serve to rile up the audience (boy, does that song rile up an audience) and provide a lively backdrop while Otis gathers together other Detroit guys to form what will become The Temptations. Time is compressed into a single song as he recruits Melvin Franklin (Jared Joseph), Al Bryant (Jarvis B. Manning Jr.), Paul Williams (James Harkness), Eddie Kendricks (Jeremy Pope) and David Ruffin (Ephraim Sykes) into the band. Then the song “Get Ready” charts the rise of the band to major player on the American pop scene.

By the time we get to “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” being performed on “American Bandstand,” it’s clear that the Temps are well on their way, and the story shifts focus in several ways. First, to Otis’ wife, Josephine (Rashidra Scott, who stops the show with her take on “If You Don’t Know Me by Now”), and their faltering marriage, and then to the bad behavior and ego flares of Ruffin and Kendricks.

Act 2 can be summed up in one line of dialogue: “The bigger we get, the more we fall apart.” Great songs like “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me” (sung as part of a TV special with Diana Ross and the Supremes), “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today),” “Just My Imagination” and “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” attest to the quality of the music being made even while band members were quitting, being fired or dying and new ones were coming in and out. By the time Otis lets loose on “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted,” it’s easy to understand why (on top of his own personal tragedy) keeping the The Temptations alive and viable could be heartbreaking work.

The end of Jersey Boys was kind of a brilliant trick in that the Four Seasons’ induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame capped a fractious era in the band’s history and this musical itself, Jersey Boys itself was the actual final chapter for the band, and we in the audience were all part of it. The ending of Aint’ Too Proud hasn’t yet figured out how to play out on that level, but that’s what out-of-town tryouts are for.

If Ain’t Too Proud isn’t perfect, it’s in phenomenally good shape. Director McAnuff, using the conveyer belt and turntables of Robert Brill’s astonishingly efficient set (with subdued and artful projections by Peter Nigrini), delivers another finely tuned machine that seamlessly blends songs with action and some of the smoothest dance moves in recent memory (Trujillo is the master of in-unison band dancing). Howell Binkley’s lights and Paul Tazewell’s costume designs convey time and place with precision and panache, and the 12-piece band headed by Kenny Seymour kicks some serious R&B butt, capturing the texture and flavor of the Motown sound and giving it fresh zest. The moment the band is revealed on stage toward the end of this 2 1/2-hour extravaganza is a well-earned thrill.

In the end, though, it’s the extraordinary cast that makes Ain’t Too Proud such a rich and rewarding pleasure. They sing, they dance, they add nuance to a fast-moving story that doesn’t have time for a lot of character detail. The way they do the things they do makes us care about the success of the band and its part in Gordy’s goal of using Motown to break down racial barriers coast to coast (and making him gobs of money while he’s at it). The voices are simply glorious – especially Sykes’ Ruffin and Pope’s Kendricks – and the blend of the boys in the band feels true to the original Temptations sound while making feel alive and not overly polished.

There’s a repeated line in the show about not dwelling on the past – the only thing you can rewind is a song – but this whole exercise is essentially a rewind. Sometimes dwelling on the past is worth it when you get new insight into the music and are able – as you do with Ain’t Too Proud – to hear it with fresh ears and a bigger heart.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of The Temptations continues an extended run through Nov. 5 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Roda Theatre, 2015 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $40-$125 (subject to change). Call 510-647-2949 or visit www.berkeleyrep.org.