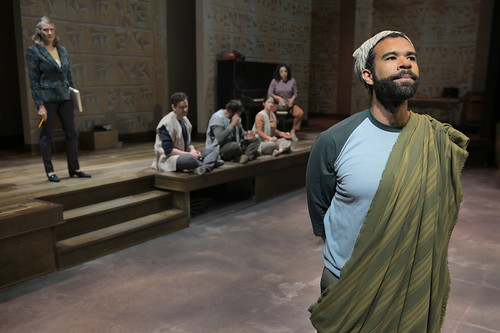

Pope Joan (Rosie Hallett), Dull Gret (Summer Brown), Isabella Bird (Julia McNeal), Lady Nijo (Monica Lin) and Patient Griselda (Monique Hafen Adams) recount their life stories at a dinner party in Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls at ACT’s Geary Theater through Oct. 13. Below: Marlene (Michelle Beck), right, interviews Jeanine (Lin). Photos by Kevin Berne

The mind of Caryl Churchill is an extraordinary place to spend an evening. Happily, this theater season, the Bay Area will see an abundance of Churchill, beginning with American Conservatory Theater’s season-opening Top Girls from 1982. [Upcoming Churchill productions include Cloud 9 at Custom Made Theatre Company, Vinegar Tom from Shotgun Players and Escaped Alone from Magic Theatre.]

Churchill is one of theater’s most bracing, original and fascinating voices. At 81, she just premiered another boundary-pushing work, Glass. Kill. Bluebeard. Imp., at London’s Royal Court, and she never seems to tire of experimenting with form. The one consistent from play to play is ferocious intelligence and curiosity and a mastery of the theatrical to both engage and entertain.

Top Girls is an interesting place to start the Bay Area’s informal Churchill festival. Nearly 40 years after its premiere, the play doesn’t feel dated, even though its time period is very much the big hair, neon colors, Maggie Thatcher world of 1980s London. In this exploration of feminism – specifically what it costs to be a woman, successful or not, in a man’s world – Churchill is in the world of fantasy, the confines of slick workplace ambitions and in the gritty, emotionally dense realm of family drama. She’s traversing, the past, present and future almost simultaneously, which is a dramatic feat to be savored.

The central character is Marlene (Michelle Beck), a committed career woman who has just landed a big promotion at Top Girls, a London employment agency. Act 1 begins with a celebration Marlene is throwing for herself in a posh restaurant’s private room (all shiny glass bricks and cool surfaces in Nina Ball’s set).

In this flight of fancy, Marelene hasn’t invited friends or family, she has invited women from history, some real, some fictional. For instance, there’s Pope Joan (Rosie Hallett) who successfully hid the fact that she was a woman in the 9th century and became pope until she rather accidentally gave birth during a procession. Then there’s Dull Gret (Summer Brown) a warrior figure from a Bruegel painting, and Patient Griselda (Monique Hafen Adams), a character from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by way of Boccaccio. Among the most talkative at the table are Lady Nijo (Monica Lin), a concubine to the Japanese emperor, and explorer/author Isabella Bird (Julia McNeal).

Though there’s a lot of talking over one another like at any dinner party involving lots of wine, each character has a moment to reflect on sacrifices they made in whatever realm of life they were in, and those sacrifices often had specifically to do with their bodies, their children and their relationships with me. What Marlene gets out of this, or how she came to choose such an eclectic guest list, is never quite clear. But we’ll learn more about Marlene’s own sacrifices at attitudes toward those sacrifices as the play proceeds to jump back and forth in time.

Director Tamilla Woodard and her cast take a while to relax into the rhythms of the dinner party. Some actors struggle with accents and with being heard over the general din. Things become more assured as the play progresses. The workplace scenes have some nice crackle to them – one scene is especially sharp, with a long-time employee of a firm (McNeal) making a bold step to find a new gig after realizing she has sacrificed any semblance of a personal life for a company that doesn’t appreciate her.

The sheen of commerce vanishes in Ball’s set as we delve more deeply into Marlene’s personal life, and the details of lower-middle-class home come sharply into focus. This is where the play lives and where all its disparate parts coalesce. Beck’s performance as Marlene crystalizes with help from fine work by Nafeesa Monroe and Gabriella Momah.

It’s interesting to think about what changes Churchill might have made – if any – were she to write Top Girls today. Would women be more supportive of one another? Would the #MeToo movement bring a sense of power or just add layers of complication? It doesn’t really matter because Churchill’s play – like most insightful human dramas – has enough depth and ingenuity to address questions beyond its time. But does it have the answers? That’s more of an off-stage, real-world matter.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls continues through Oct. 13 at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $15-$110 (subject to change). Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org.