EXTENDED THROUGH OCT. 23!

Jud Williford (right) and Bill Irwin make a delightfully dynamic duo in ACT’s Scapin. Below inset, Irwin, and further below, the Scapin ensemble. Photos courtesy of www.kevinberne.com

If you want to see what funny looks like, you should see Bill Irwin in a comedy. In recent years, he’s been fairly serious, what with his stage work in shows like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (a Tony Award-winning turn opposite Kathleen Turner) or The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (opposite Sally Field) and his movie work as a dedicated dishwasher-loading dad in Rachel Getting Married.

But Irwin is a clown in the purest sense. The Bay Area knows him as one of the founders of the Pickle Family Circus, and his alter ego, Willy the Clown, is as beloved as they come.

We’ve seen Irwin on the American Conservatory Theater stage in the last few years, in his luminous Fool Moon project with David Shiner and the conundrum of Beckett’s Texts for Nothing, but his return as the title character in Moliere’s Scapin, ACT’s season opener, is reason to cheer.

As dexterous and expressive a physical comedian as you’ll ever see, Irwin’s genius is that he’s not a show off. He’s a reveler. He revels in his every movement and rubber-faced grimace. He delights in his interactions with the other actors on stage and the smiling faces in his audience. It’s not all about him (though it easily could be) – it’s about the collective experience.

That’s reason enough to see Scapin, which is merrily directed by Irwin himself and features an irreverently updated script by Irwin and Mark O’Donnell (author of the wonderful novel Getting Over Homer and a Tony winner for his work on Hairspray’s book).

Without seeming to try too hard, Irwin does everything with humor. His walk is more like falling down, dancing and melting, all at the same time. His face never stops commenting on everything happening around him, and his verbal timing is just as sharp as it needs to be.

Irwin’s Scapin, a farcical fracas of winsome lovers and greedy fathers, is a free for all with its references to ACT subscribers, Inception, Robert DeNiro and gay marriage. Irwin and O’Donnell have stripped Moliere’s script to its essence, laying bare all the conventions of the farce, from the unbelievable consequences (helpfully pointed out by giant signs) to the requisite chase.

It’s all just so much silliness – brilliantly outfitted in the outrageously rich creations of costumer Beaver Bauer – but Irwin rises to the top of the fray like cream. Ably and comically backed by musicians Randall Craig and Keith Terry (both former Pickles), he elevates the rest of the ensemble, which includes some fine work by Geoff Hoyle (another old Pickle), Gregory Wallace and Steven Anthony Jones.

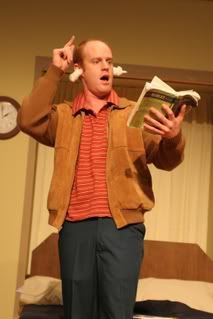

But the truly wonderful surprise is Jud Williford as Sylvestre, one of Scapin’s servant peers. Apparently Williford and Irwin bonded several years ago when Williford was an ACT MFA student and Irwin was conducting a master class. Irwin knew then that Williford would be a brilliant second banana in Scapin, and he is.

In fact, he’s almost as good as the top banana. Sylvestre is a juicy role, and Williford makes the most of it. He gets loads of laughs, but he’s also warm and human.

The surprise isn’t that Williford is good. He’s always good – look no further than his recent performance in the title role of Macbeth at the California Shakespeare Theater. No, the surprise is that he’s so vibrant and funny, especially compared to the incomparable Irwin. The two have great chemistry, and it’s nice to see that the king of comedy now has a clown prince.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Moliere’s Scapin continues an extended run through Oct. 23 at the American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $10-$90. Call 415 749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org for information.

The production, which will bow in the 2009-10 season, will star 17-year Stratford veteran Seana McKenna in the title role.

The production, which will bow in the 2009-10 season, will star 17-year Stratford veteran Seana McKenna in the title role.

While working on a production of The Imaginary Invalid in Philadelphia (not to be confused with the more recent ACT “Invalid” in which he played the same role), Williford read The Triumph of Love for the first time, and his response to Price Aegis, the role he would be playing, was: “Oh my gosh, this is going to be a cakewalk.”

While working on a production of The Imaginary Invalid in Philadelphia (not to be confused with the more recent ACT “Invalid” in which he played the same role), Williford read The Triumph of Love for the first time, and his response to Price Aegis, the role he would be playing, was: “Oh my gosh, this is going to be a cakewalk.”