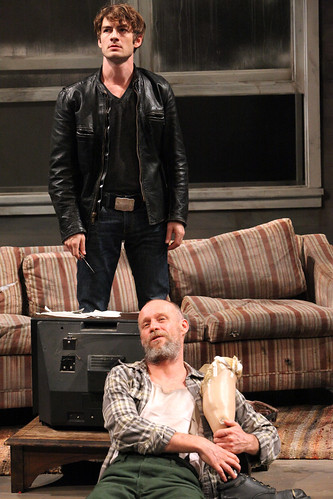

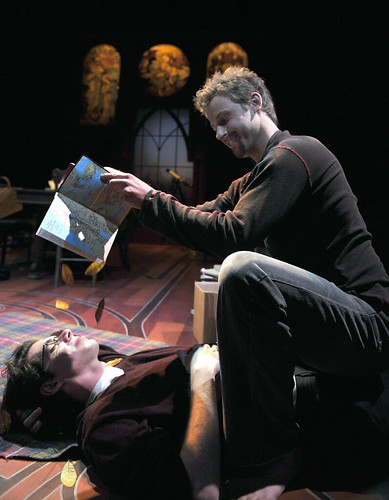

The cast of American Conservatory Theater’s The Realistic Joneses includes, from left, James Wagner as John Jones, Allison Jean White as Pony, Rebecca Watson as Jennifer Jones and Rod Gnapp as Bob Jones. Below: Watson’s Jen and Gnapp’s Bob hang out in the backyard in Will Eno’s comic drama. Photos by Kevin Berne

The topic is: things that have happened. That broad, yet somehow quite specific, statement comes from a character in Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses now on stage at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater. Another broad yet specific topic might be: lives that are lived.

Eno is one of those playwrights whose gift seems to be making raising the bizarre, often absurd experience of human existence to the level of cosmic grace and beauty. How he does that exactly is a bit of a mystery, as it should be, but it’s on fully display in Joneses even more than it was in several of his remarkable earlier plays such as Tragedy: A Tragedy and Middletown. Eno has a dash of Samuell Beckett, more than a pinch of Thornton Wilder and a heaping helping of any smart stand-up comedian you’d care to name.

With The Joneses, Eno takes two couples, both with the last name Jones (my grandfather once told me everyone was born Jones but only the good ones stay that way) and lets them reflect on each other and affect one another. A quiet, four-person play would seem to be out of place on the massive Geary stage, but that is not the case. As director Loretta Greco is well aware, Eno is micro and macro. There’s an epic quality to his intimacy, and that’s reflected in Greco’s beautiful production, which features a set by Andrew Boyce that offers the backyards of two homes in suburban American (somewhere near the mountains and sea, we’re told). There’s a massive tree canopy that allows some visibility of the stars, and that’s important. As I said before, this play opens up in its curious way, to the cosmic. Size matters here, and the production makes the vastness count.

One quiet night, interrupted only by the rustling and chirping of night sound, Bob and Jennifer Jones (Rod Gnapp and Rebecca Watson) are outside at their picnic table. You could say they were talking, but that becomes a topic of discussion: are they talking, really talking? Or are they “throwing words at each other.” Just as they might be veering from throwing to talking, they are interrupted by new neighbors, Pony (Allison Jean White) and John (James Wagner), bearing greetings and a bottle of wine.

From here, we discover interesting connections within this quartet as Eno shuffles them up – a grocery store meeting here, late-night backyard encounter there – and casts a shadow of mortality in the form of an illness one character calls “the Benny Goodman Experience.” There is nothing “normal” about this play, not its rhythms, not its character interactions, not its trajectory. And yet, as it proceeds through its one hour and 45 minutes, it gains a weight and a poignancy that is surprising, especially given how many good laughs it offers. The wonderful cast and Greco can take a lot of credit for that, but the real architect here is Eno.

The engine of the play is John, a man who is searching and struggling and suffering. The path his thoughts, and consequently his words, take give rise to much of the humor because he’s the king of the unfiltered non sequitor. He says of his wife, “What my lady wants, with some huge and basic exceptions, my lady gets.” Or when he asks Jennifer if she has any brothers, Jen answers that she has two half-sisters. “So that sort of equals a brother,” John says. He also points out later on that “even a hundred-year-old fake is an antique.”

Pony and John have their comically absurd moments as well. Pony, in a moment of frustration with her life, says, “I feel like I should go to med school or get my hair cut or something.” Or something. Then she muses on other tracks her life might have taken: “I probably would’ve overdosed on drugs, if I’d gotten into drugs and then taken too many.” Only Jennifer seems to be the fully anchored grownup in the group, the mother figure who is as lost and in search of something as the rest of them. She just functions in everyday life at a higher level than they do.

The Realistic Joneses is, in its subdued, humorous way, stunning, a deeply felt examination of what we do with this life and these brains and these souls. The ending, as surprising as everything else in the play, brought to mind the comedian Rita Rudner’s deep philosophical query: “Any questions? Any answers? Anyone care for a mint?”

FOR MORE INFORMAITON

Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses continues thorugh March 12 at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $25-$105 (subject to change). Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org.