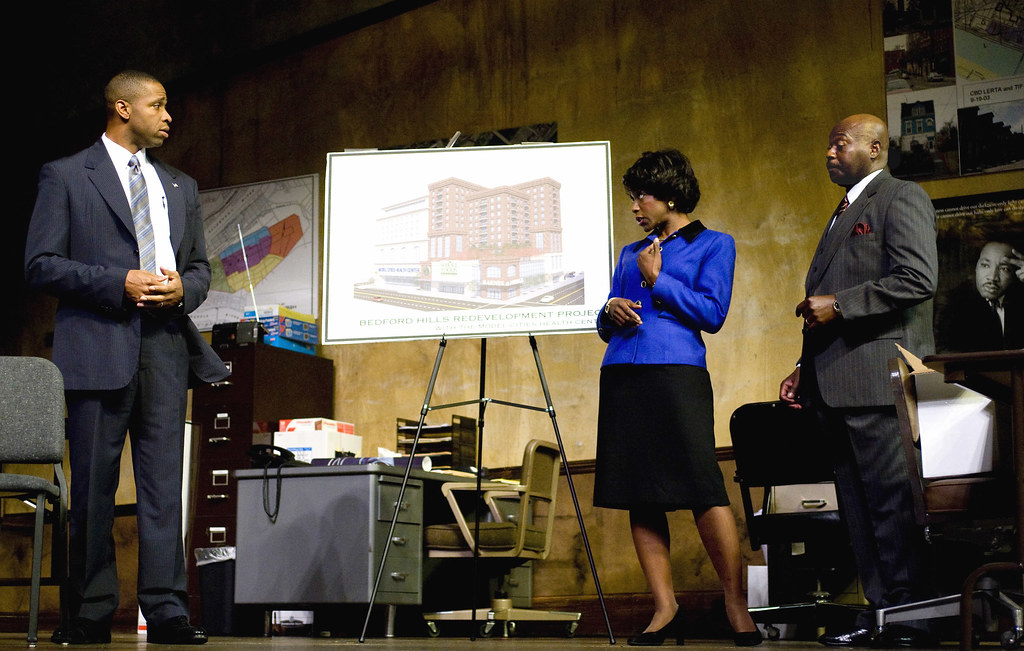

Aldo Billingslea (left) is Harmond Wilks, C. Kelly Wright (center) is Harmond’s wife, Mame, and Anthony J. Haney is Harmond’s business partner, Roosevelt Hicks, in August Wilson’s Radio Golf at TheatreWorks in Mountain View. Photos by Mark Kitacka.

Superb cast tunes up Wilson’s `Radio’ at TheatreWorks

««« ½

Even the prodigious talents of August Wilson have a hard time making the ’90s interesting.

Radio Golf, Wilson’s final play and the last piece of his extraordinary cycle of plays documenting African-American life in each decade of the 20th century, receives its Bay Area premiere in a tightly focused, incredibly well acted production from TheatreWorks in Mountain View.

Perhaps because we have the least distance from the ’90s, as opposed to other plays in Wilson’s cycle (such as “Fences” in the ’50s or “The Piano Lesson” in the ’30s), it’s difficult to feel the dramatic weight of a decade that is best remembered for e-mail, the Internet and little else.

Curiously, there’s not a computer to be seen on Erik Flatmo’s set – a “raggedy,” as one character calls it, office space in Pittsburgh’s Hill District that was once the height of elegance with its embossed tin ceiling. The year is 1997, and the space is being used as home base for the Bedford Hills Redevelopment Project, an ambitious attempt to obliterate the blight of the black district’s poverty and hard times and introduce apartment complexes, a Starbucks, a Barnes and Noble and, of course, a Whole Foods.

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

There’s a lot of business talk in Radio Golf – maybe that’s another reason the ’90s are hard to enliven because the decade was all business – but with all the exposition of Act 1 out of the way, we get to the heart of what Wilson seems to be after here.

As time rolls on, and as “progress” pushes forward, we tend to want to deny – or at least ignore – the past rather than deal with it. But without the past, how do we know what our success really is? And without a clear view of where or who we’ve been, how do we know we’re aiming for success for the right reasons?

These are the issues faced by Harmond, a straight-laced, follow-the-plan kind of guy. His gorgeous, successful wife, Mame (C. Kelly Wright), has helped formulate the plan to get him into the mayor’s office, and together they are going to head all the way to the Senate.

But just as the plan is kicking into gear, the past shows up in the form of two men. One, Old Joe (the superb Charles Branklyn), is slightly crazy and has questionable motives, but he is deeply rooted in the past of the Hill District and even more rooted in Harmond’s past than he knows.

The other is Sterling Johnson (L. Peter Callender), a self-educated, hard-working man who brings a big dose of reality with him wherever he goes. Wilson, in a rather lazy narrative approach, makes him read from the newspaper a few too many times, but Sterling has the kind of integrity that makes businessmen and politicians nervous.

Director Harry J. Elam Jr. has a hard time kicking the long first act into gear, but in Act 2, the play and the actors catch fire because Wilson is focusing less on plot and much more on character.

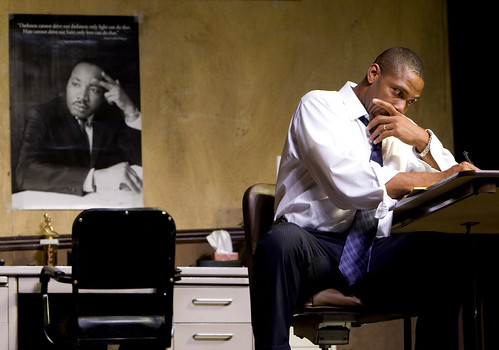

With his open, honest face, Billingslea is superb as Harmond. There are dark currents coursing through this ambitious man who adopts as his election slogan: “Hold Me to It.” Faced with compromise and injustice, Harmond has to find some sort of balance between his ambition and his integrity.

Billingslea has an incredible scene with Wright, who never makes a misstep as the supremely well put together Mame. The couple watches their goals and their dreams of a perfect life in politics crumble around them. And in this one scene, they have to determine their future as a couple and what their past measures up to in the present.

There’s another extraordinary scene in the second act, this one between Haney’s Roosevelt and Callender’s Sterling. The two men – from opposite ends of the African-American male spectrum – clash in a profound way, each calling the other names and attempting to define one another through blame and accusation. It’s a difficult, chilling scene, and through it, Wilson cuts right to the heart of why race in this country has been for more than a century, and will continue to be, such a complex, polarizing issue.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Radio Golf continues through Nov. 2 at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts, 500 Castro St., Mountain View. Tickets are $23-$61. Call 650-903-6000 or visit www.theatreworks.org.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.