EXTENDED THROUGH NOV. 30

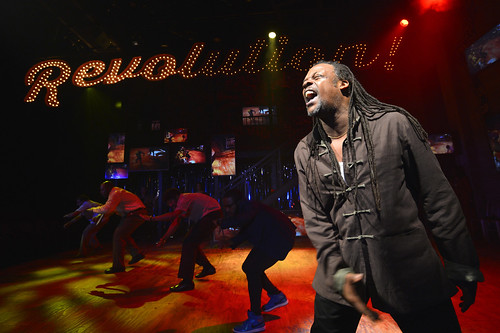

Steven Sapp (right) as Omar leads an ensemble cast in UNIVERSES’ Party People, a fusion of story and song that unlocks the legacy of the Black Panthers and Young Lords at Berkeley Rep. Below: J. Bernard Calloway (left, asBlue), Mildred Ruiz-Sapp (Helita, background), and C. Kelly Wright perform in the extraordinary historical musical number that opens Party People. Photos courtesy of kevinberne.com

There are ovations and there are ovations. The opening of an envelope gets a standing ovation these days, so the stand and clap doesn’t really mean much anymore. But at the opening night of UNIVERSES’ Party People at Berkeley Repertory Theatre, the audience was instantly on its collective feet at show’s end, applauding thunderously, shouting and hooting. The appreciative cast bowed, expressed gratitude and exited the stage. The house lights came on, and still the clamor continued. A few audience members exited the theater, but mostly the noise grew in intensity until the surprised cast had to return to the stage and bow yet again.

It seemed a fittingly over-the-top reaction to an ambitious, over-the-top show that leaves you feeling moved by the wheels of history and the vagaries of the human heart.

Party People was commissioned by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival as part of its American Revolutions: The United States History Cycle and had its premiere there in 2012. Created by UNIVERSES, a creative and social force comprising Steven Sapp, Mildred Ruiz-Sapp and William Ruiz, aka Ninja, and director Liesl Tommy (who is also Berkeley Rep’s associate director), the show is ostensibly about the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, two revolutionary groups born of the tumult of the 1960s that aimed to change the world and, in the face of powerful opposition, ultimately failed in their mission.

What’s extraordinary about Party People is how powerfully it works on its own terms. It can be kaleidoscopic and collage-like as it blends music (original compositions by Broken Chord) and video (live and recorded, beautifully designed by Alexander V. Nichols) and self-conscious art making with concise and incisive history lessons and, perhaps most importantly, human-scale stories that, individually and collectively, bring it all together and connect the audience to the past, present and future of this country.

That’s not to say that Party People is perfect – it seems unlikely that something this sprawling, rambunctious, fiery and beautiful could be. Some of the dramatic monologues are too long and don’t connect as powerfully as they might, but missteps are rare in this 2 1/2-hour fantasia on race, revolution and justice. From the extraordinary opening musical number that creates historical context for this intertwining story of the Panthers and the Lords, we become caught up in the flow of revolutionary zeal – free meals for kids, education reform, fighting police brutality and racism, recovery programs – and quickly see how egos and conflicts and violence can explode the truest of intentions.

On an urban two-level set (sturdy and graffiti covered design by Marcus Doshi who also designed the dazzling light show) covered with video monitors, we slip in and out of the present, where two children of the movement, Malik ( Christopher Livingston) and Jimmy (Ruiz), are processing their complicated legacy in a multimedia show. It’s opening night, and they have invited a wide assortment of personalities from back in the day, some of whom bring troubled and troubling histories with them.

Tension and conflict run high as these former revolutionaries (some are still active, even if only in their own minds) take an uneasy stroll down a memory lane littered with ideals and betrayals, rage and regret. This mash-up of nostalgia and minefields can veer to the melodramatic, but then real fire bursts forth as when C. Kelly Wright as Amira, a former Panther and wife of a Panther wrongly convicted and imprisoned for the murder of a police officer, lashes out at Malik and Jimmy and their generation of naval-gazing, Internet-obsessed “revolutionaries.” But then Malik lashes right back, and it becomes clear that the generation gap is a major force affecting communication and perception in this particular crowd.

So many sections of the show stand out, not the least of which is an incredible monologue by Sapp as troubled former Panther Omar accompanied by the other men in the cast exerting themselves in a powerfully athletic (and seemingly exhausting) display of the choreography by Millicent Johnnie. There are also some gorgeous voices to be savored here from Ruiz-Sapp, Amy Lizardo, Reggie D. White and Sophia Ramos.

As relevant and as thought-provoking as it is, Party People is also mightily entertaining. Humor, music and dance go a long way toward keeping this narrative afloat, even when the weight of history and sacrifice bear down heavily. These may be some of the most invigorating sad stories you experience. History is not over-explained, and nothing is emotionally tidy. We don’t get a concisely wrapped up ending, but we do feel like connecting with the past makes for a more powerful present and, in glimmers, a more hopeful future.

[bonus interview]

I interviewed UNIVERSES member Steven Sapp about creating Party People for a story in the San Francisco Chronicle. Read the feature here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

UNIVERSES’ Party People continues an extended run through Nov. 30 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Thrust Stage, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $29-$89 (subject to change). Call 510-647-2949 or visit www.berkeleyrep.org.

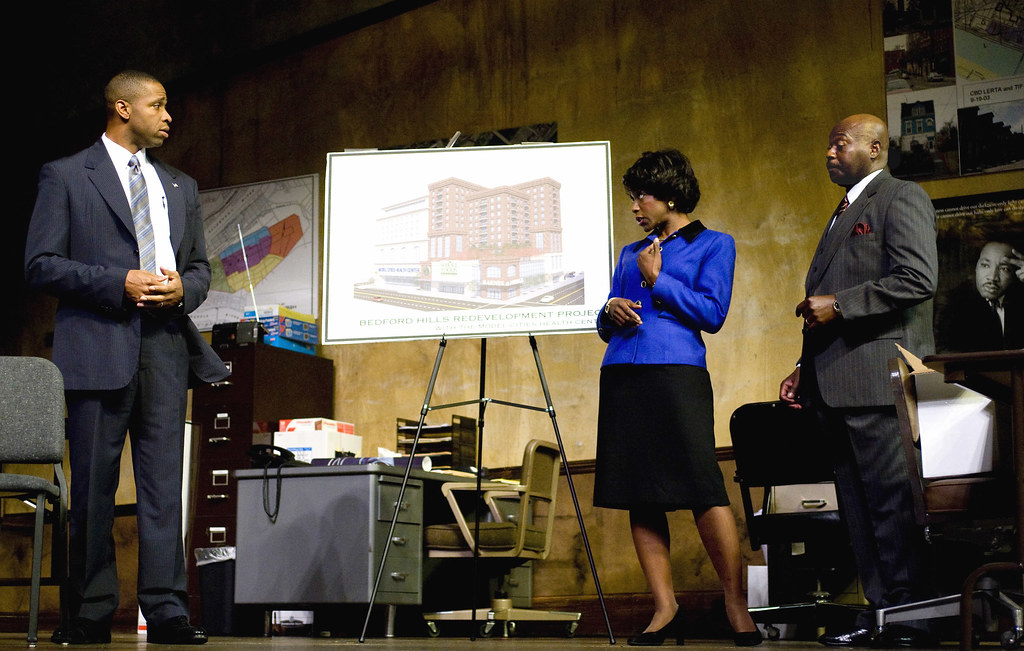

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.