The elegance of simplicity creates space that allows for the profound reward of listening, truly listening. Peter Brook probably wouldn’t want to be labeled a legendary director, but he is. His more than 70-year career is festooned with innovation, genius and the fascinating arc of an artist following his muse rather than his ego. In Battlefield, now at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, the 92-year-old director achieves something sublime in its stripped-down beauty and incredibly moving in its poetic grappling with the meaning of life.

In 1985, Brook, along with collaborators Jean-Claude Carrière and Marie-Hélène Estienne, debuted a mammoth nine-hour stage adaptation of The Mahabharata, an ancient Sanskrit poem depicting an epic battle of good versus evil. In 2015, Brook and his collaborators revisited that massive text to explore what happened after the war was over. Battlefield is only just over an hour in length, and it is performed by four actors and a musician. Though its elements are simplified, its power is extraordinary.

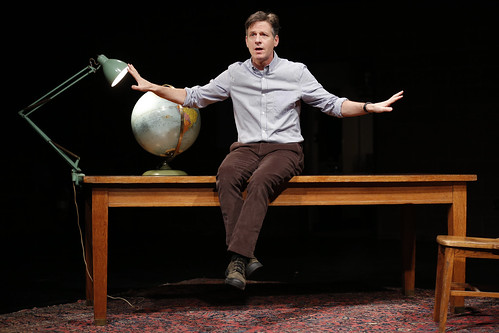

Theater at its most elemental is humans telling stories to other humans, the very means by which we realize our humanity: we sit in awareness, together, of our shared awareness. Battlefield is at once epic and personal, mythical and real, which is to say this is storytelling at is best.

With a cost of what we are told is millions of lives, the battle between the Kauravas (descended from demons, so, the bad guys) and the Pandavas (descended from the gods, hence, the good guys) is ended, and those left behind are taking stock and attempting to come to terms with what it was all about. One of the ways they deal with weighty issues like grief, guilt and despair is to tell stories – stories about a boy and a snake, about a worm in the road, about choices made in youth, about redemption and destiny.

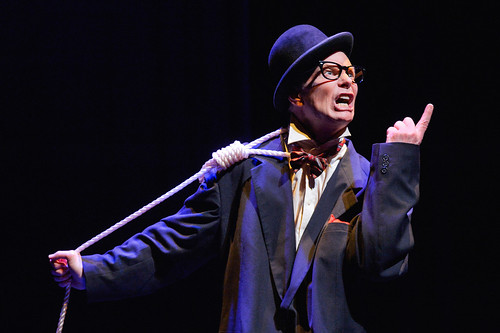

You don’t have to know anything about The Mahabharata to fully enjoy this gorgeous production. The actors – Carole Karemera (who is succeeded by Karen Aldridge beginning May 16), Jared McNeill, Ery Mzaramba and Sean O’Callaghan – are such gifted storytellers that all you have to do is listen and watch the way they transform in the simplest of ways using bright, blue, and red and gold swaths of fabric as if they were enchanted cloaks. Musician Toshi Tsuchitori adds to the rhythmic thrust of the action on stage and plays a very important role toward the end of the show when the secret of life is revealed (spoiler alert: the answer involves a rather profound silence).

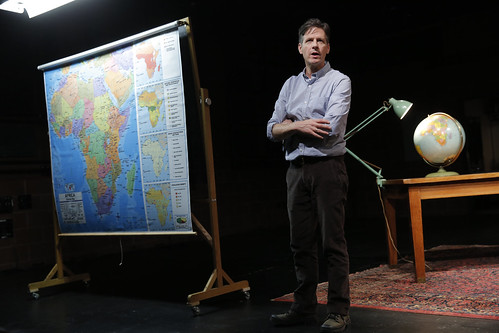

Brook’s most famous book is called The Empty Space, and it’s clear from his work here, just how powerful that empty space can be when it is filled with just enough elements to create magic: actors who supply just enough emotion, costumes (by Oria Puppo) that are graceful but commanding, lights (by Philippe Vialatte) that shape space as much as they illuminate story, and a text that has the power to transcend a specific culture by addressing the very core of what it means to be alive on the planet, in battle or out.

As a director, Brook doesn’t lecture, doesn’t cheerlead, doesn’t judge. He lets the story be the story, and in this case, that story is about how humans are caught in a never-ending cycle of causing grief for themselves and damage for the world they inhabit. When they win, they lose, and vice-versa. There’s a simple level of good vs. evil and then layers of complication underneath, all presented with such focused simplicity that its beauty can be breathtaking.

Battlefield is theater (and life) distilled down to an essence of gentle reflection. This isn’t the Greeks beating their chests and screeching at the heavens. This isn’t Shakespeare orating beautifully about the vagaries of life. It’s sad humans contemplating their role and function in a baffling universe and grappling with that unknowable shape shifter known as destiny.

[bonus video]

Just for kicks, you can watch the nearly six-hour television adaptation of The Mahabharata on YouTube!

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Peter Brook’s Battlefield continues through May 21 at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $20-$105. Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org.