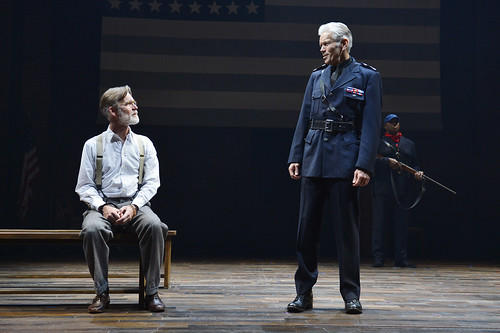

Yul (Skyler Cooper) and Rena (Maria Candelaria) grow closer contemplating life outside Farm Company’s rules and regulations in Crowded Fire’s world-premiere production of Christopher Chen’s A Tale of Autumn at the Potrero Stage. Below: San (Nora el Samahy) and Xavier (Christopher W. White) have a long history and common enemies. Photos by Cheshire Isaacs

Who are the good guys/bad guys? What truth lies behind smokescreens and lies? And when good guys resort to immoral behavior, doesn’t that make them bad guys, thus leaving a dearth of good guys and obscured truth?

San Francisco playwright Christoper Chen’s world-premiere A Tale of Autumn, a commission from Crowded Fire Theater, is all about good gone bad and bad gone worse. Imagine Google, Oprah and the U.S. Government wrestling with notions of altruism and greed and you get some idea of what Chen is up to here.

Staged by director Mina Morita – also Crowded Fire’s artistic director – on what looks like a ritual platform carved of stone with a few chairs and tables straight from the Flintstone collection (design by Adeline Smith), the primitive space In the Potrero Stage is enhanced by elegant white drapes that effectively catch the lights (by Ray Oppenheimer and projections (by Theodore J.H. Hulsker, who also contributes sound design) and convey a sense of modernism at odds with the primal furnishings. This play feels vaguely futuristic – there’s talk of phones, for instance, but electronic devices are ever seen – and the characters dress in a more elegant version of Star Wars/Star Trek finery (designs by Miriam R. Lewis).

At the center of the story is a massive agricultural outfit called the Farm Company that aims not to be the usual corporate behemoth raping the land and pillaging the people for profit. Not unlike Google’s “don’t be evil” mandate, Farm Co. has grown so big and so powerful that it can’t help being a little (or a lot) evil. The founder of the company has just died, and her successors are at a crossroads, both moral and financial. There’s an opportunity to make the company even more powerful so it can do more good for more people (according to one candidate to fill the CEO position) or they can, according to another candidate, make the shareholders happy by simply doing whatever it takes to beef up the profits.

San (Nora el Samahy) seems to be the idealist CEO candidate who espouses following a vaguely cult-y notion of the founder’s philosophy known as “The Way,” while Dave (Lawrence Radecker) is more of a capitalist pig type. But nothing is quite what it seems when massive amounts of money are involved. Plots are hatched, crimes are committed in the name of doing what’s best for the company and its customers and goals are achieved at the cost of people dying (unintentionally, or perhaps, intentionally).

Just another day in the good ol’ U.S.A.

In this future world, Big Agriculture has taken over pretty much everything, including what people are allowed to plant at their own homes. One rebel (Michele Apriña Leavy, who also plays a scary member of the Farm Co. board of directors) grows a kind of wheat that has been outlawed just so she can make a delicious loaf of bread. It’s that kind of cruel future – one that messes with our carbs and our childhood memories of home cooking. When her rebelliousness is quashed, her friend Yul (Skyler Cooper) partners up with Rena (Maria Candelaria) a former Farm Co. employee who has suddenly become an investigative journalist aiming to expose corruption at the highest level. She even manages to get into a prison cell with a supposed terrorist (Christopher W. White in a sharp-edged performance).

So, is A Tale of Autumn satirical? Sometimes, especially when the character of Dave is involved (he’s like something out of the HBO show “Silicon Valley”). Is it a foreboding thriller? Sometimes but not nearly enough. Though there are lives and global economies at stake here, the tension doesn’t feel very tense. Is it a parable a bout the depthless greed and idiocy of humankind? Yes, and that’s where it’s most effective. The whole thing about the former employee becoming a journalist and somehow gaining access to people at the highest corporate levels feels implausible at best. There’s a lot of plot activity in this two-plus-hour play, but none of it carries much weight beyond the cerebral exercise of comparing the action to events of our own troubled times.

The most interesting character here is Mariana (Mia Tagano), a division leader at the company whose loyalty is kind of a gray area. She thinks San’s goal of realizing the late founder’s true vision for the company is a good one, even if it means the ouster of Dave, who happens to be her lover (even though Dave apparently lives with his male lover, Gil, played by Shoresh Alaudini. It doesn’t seem to take much to get Mariana to betray confidence, though when she has her final change of heart, we don’t know how or why, only that it happened, which feels dramatically inert. There’s something very interesting about how people change their minds based on how hard (or easy) it might be to affect change of one kind or another,

and though we see a bit of this process from other people, it would be interesting to be more inside Mariana’s head.

This feels like a new play that hasn’t yet found its way. The ending comes so abruptly it seems more a stopping point than an actual ending. If a tale of winter is hot on the heels of this Tale of Autumn, it promises to be more confusing than chilling.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Christopher Chen’s A Tale of Autumn continues through Oct. 7 at Potrero Stage, 1695 18th St., San Francisco. Tickets are $10-$35. Call 415-523-0034, ext. 1 or visit www.crowdedfire.org.