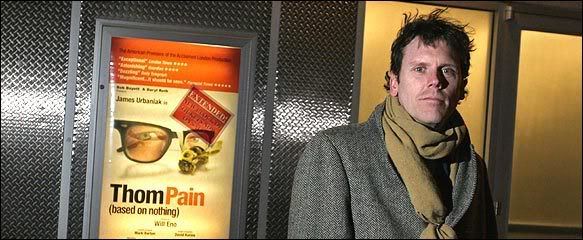

Guy (Tony Hale) asks the audience to follow him in an exercise of imagination in Will Eno’s Wakey, Wakey performing at ACT’s Geary Theater. Below: Lisa (Kathryn Smith-McGlynn) stretches as Guy rests. Photos by Kevin Berne

When you write about theater, you tend to take notes while watching the show whenever a line or a moment triggers the part of your brain that says, “Oh, I’d like to mention that later.” During Will Eno’s Wakey, Wakey now at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, the first half had me writing so fast and furiously I finally just had to stop writing entirely and simply absorb the show.

This isn’t surprising in that Eno is one of the most interesting playwrights in the theaterverse. He’s weird and brilliant, funny and deeply humane. Because there can be an oblique and highly theatrical quality to his work, he has often been compared to Beckett, but for me, I feel more Thornton Wilder (somewhere between The Skin of Our Teeth and Our Town). He wrestles in creative and insightful and surprising ways with what it is to be alive and how we’re all connected by the knowledge that none of us is getting out of here alive and that we could all probably be doing better when it comes to being aware of our lives as we’re living them.

Wakey, Wakey,, like other Eno works, defies easy description. There are people and things happen, but where they are and what exactly they’re doing isn’t clear. And it doesn’t need to be. We’re all here and this is happening. Director Anne Kauffman eases us into this world, helps us relax and just take the play as it comes without expectations that this is going to follow the rules and rhythms of plays we’ve experienced before.

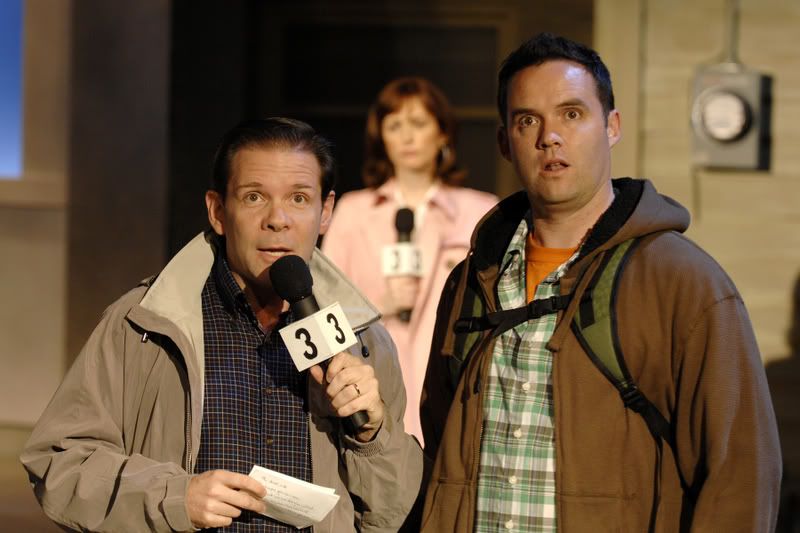

The play begins with a prologue of sorts, The Substitution, about a community college driver’s ed class where the substitute teacher (Kathryn Smith-McGlynn) shakes things up by not behaving the way the students expect her to and ends up giving them something far more interesting (if inscrutable) than the rules of the road.

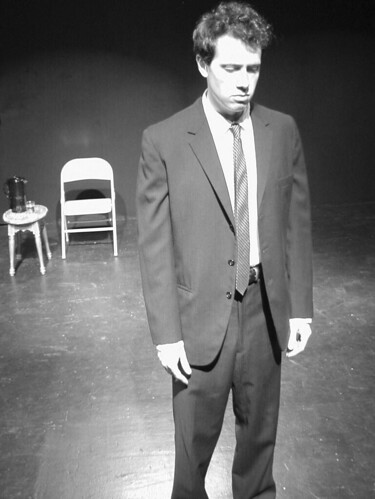

Then the play begins in earnest with the appearance of Guy (Tony Hale), about whom we know nothing except that our first encounter with him finds him face down on the floor minus his pants. Seconds later, his pants are on, he’s sitting in a wheelchair and he’s talking directly to us.

Apparently we’re all here for some sort of presentation (well, yes, isn’t that what a play is?). Guy is offering, with the help of some notecards, a semi-inspirational TED-ish talk about the nature of time and about how this is not really how it was supposed to be. The setting (by designer Kimie Nishikawa) is a nondescript auditorium or multipurpose room in some sort of civic or educational institution or perhaps a place where people live together or are receiving treatment. Again, details are sketchy and it doesn’t really matter (although I have theories, and I’m certain they’re all 100% accurate).

What Guy does (or did) before being in this room with us is not known. If he has connections to other people (spouse, child, friends), that also remains a mystery. He’s going to engage us as best he can and share a little of what he knows about life but with lots of distractions and asides. Hale’s basic likability is essential here. We know and love the actor from his incredible work making misfits lovable on “Arrested Development” (Buster) and “VEEP” (Gary) and most recently as the voice of Forky in Toy Story 4 (talk about an existential crisis). None of the quirks we might recognize from other characters inform Guy, who is clearly a kind person if somewhat frustrated by his current situation. So even though we don’t know much about Guy, we like him and connect with him and want him to succeed in this endeavor, even as it seems to grow increasingly difficult for him.

There is another character, possibly someone we met in the prologue (or someone else entirely), and that character helps clarify (a little) what we’re actually witnessing.

Wakey, Wakey feels like more of an experience than a play, one that lingers as a feeling (or an avalanche of feelings) rather than as conundrum we have to pick apart and solve. There’s a lot about death here – does the title refer to a gentle way of rousing a sleeping child or is it a play on the gathering we have after a funeral? – and as a result, it’s positively hopeful and life affirming. This rich experience – barely 90 minutes – is also funny, moving and inspiring. There are so many things we can do with the limited time we’re given. Absorbing Wakey, Wakey would be a good use of that time.

[FOR MORE INFORMATION]

Will Eno’s Wakey, Wakey continues through Feb. 16 at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $15-$110. Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org.

Wolohan was voted by American Theatre magazine as one of the country’s seven actors “worth traveling to see,” and I wholeheartedly agree.

Wolohan was voted by American Theatre magazine as one of the country’s seven actors “worth traveling to see,” and I wholeheartedly agree.