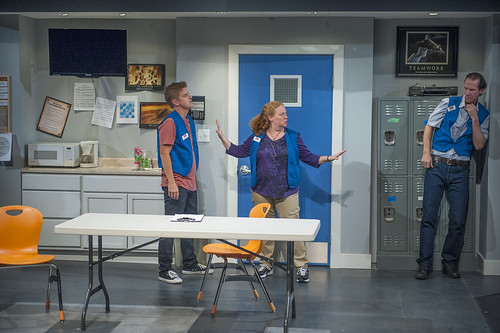

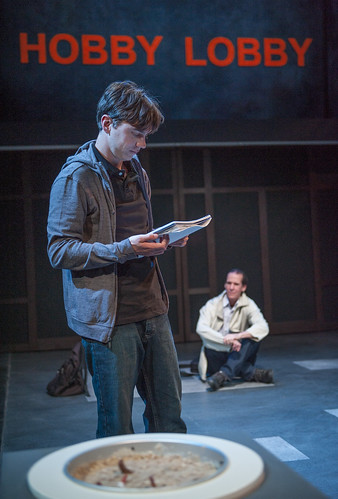

Sam (Rebecca Dines, left center) sends Jonathan (Devin O’Brien, center right) on an errand as Angie (Laura Jane Bailey, right) enjoys some fine cognac and Beth (Jamie Jones, left) pours herself another one in the Bay Area Premiere of Marisa Wegrzyn’s Mud Blue Sky at Aurora Theatre Company. Below: Jones as Beth straightens the bowtie worn by O’Brien’s Jonathan on his bizarre prom night. Photos by David Allen

There’s easy comedy and titillation to be had in choosing to explore the lives of flight attendants. You could blithely whip up a story detailing the lives we imagine those high-fliers live, with their easy access to great cities, hot coworkers and the occasional randy passenger. That story might be fun, but in truth, the days of “coffee, tea or me” are long past, and flying is a grind for everyone, from passengers to crew, and that may actually be the more interesting story.

Marisa Wegrzyn’s Mud Blue Sky, now in an extended run through Oct. 3 at Berkeley’s Aurora Theatre Company, tries to have it both ways – swinging comedy, down-to-earth drama – and succeeds mightily. There are farcical elements in play, and cognac and marijuana are enjoyed, and there are some hearty, satisfying laughs to be had, but what lingers in the air after the show is a sense of connection, comradeship and workaday resilience among the characters.

Unlike those “flight”sploitation movies of the ’60s and ’70s, there is nothing glamorous about the two flight attendants we meet at a cheap motel in the purgatory between O’Hare and Chicago. Beth (Jamie Jones) has a terrible back and won’t do anything about it except self-medicate with pot, which she gets from a teenage supplier, Jonathan (Devin S. O’Brien) somewhere behind the motel. Sam (Rebecca Dines) seems to be more of a partier. She wants to go to the bar, meet up with an old friend and strap on the old feedbag at IHOP (“Bacon!”). But she’s not as breezy as she seems. She’s got a 17-year-old son back at home in St. Louis, and he’s on his own an awful lot, given her schedule, and that weighs on her.

What’s so interesting about Wegrzyn’s play is that it really does feel like a slice of life we don’t get to see very often. For instance, Beth is what’s known as a “slam locker.” She gets to the hotel room, slams the door and locks it. But on this night, Beth’s locked door won’t be enough. She’s drawn out to meet Jonathan and make their usual deal. The high schooler is wearing a tux because it’s prom night, and he’s available to help Beth score because he has been ditched by his date.

Details about the lives of these characters begin to trickle out, and while there’s not high drama here, there’s compassionate drama filled with day-to-day realities of just trying to get through and deal with the people you have to deal with and maybe something more (better?). We’ve all encountered flight attendants who seem weary or who have their heads somewhere else, and taking a peek into the fictional lives of these flight attendants fills in the back story very nicely.

As the evening wears on, Jonathan ends up in Beth’s hotel room (the set by Kate Boyd is so perfect you want to call housekeeping for an emergency deep cleaning) and there’s a new guest: Angie (Laura Jane Bailey), who trained with Beth and who used to be a key member of the crew. But she gained some weight and was promptly fired. She’s been living with and taking care of her mother since and hasn’t been able to find another job.

Bailey’s Angie has a long monologue toward the end of this 95-minute one-act, and it’s as sweet as it is heartbreaking. She misses the connection with her former co-workers and passengers. She longs for the chance encounters with fun and kindness and outrageousness that her job afforded her, and this short visit with her old friends (who have not been great about keeping in touch since her departure) is a boost to her psyche.

Director Tom Ross does superb detail with work with his wonderful actors here. Nothing feels rushed, and the actors give us characters whose lives feel lived in. That’s why the humor can spark so effectively one minute and the pathos can register deeply the next.

Jones’ weary Beth keeps trying to be a stick in the mud, but fun and empathy continually prevent her from giving in completely to her misery. She has a real (if somewhat reluctant) connection with the Eeyore-like Jonathan, expertly played by O’Brien, whose slumpy posture and teenage galumphing are scarily accurate and endearing.

Dines’ Sam is peppery and bright, which is to say she’s bursting with energy, but she’s also prone to stinging from time to time. Sam’s participation in the evening’s festivities takes a surprising, provocative turn that takes yet another surprising turn. Credit Wegrzyn’s intriguing script for keeping us guessing as to where this story will fly next.

Mud Blue Sky has the crackle of good television (a compliment in this golden age of television) but the rhythm and heft of good theater. These skies are friendly enough, but it’s the turbulence that really matters.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Mud Blue Sky continues through Oct. 3 at Aurora Theatre, 2081 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $32-$50. Call 510-843-4822 or visit www.auroratheatre.org.