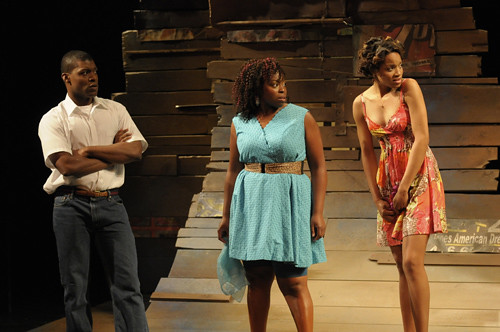

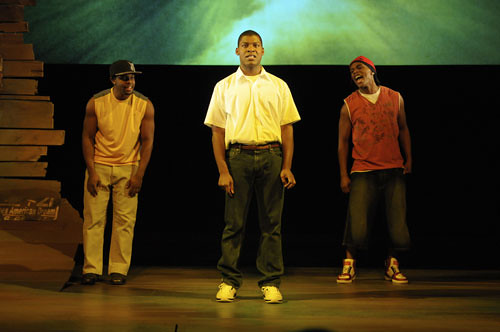

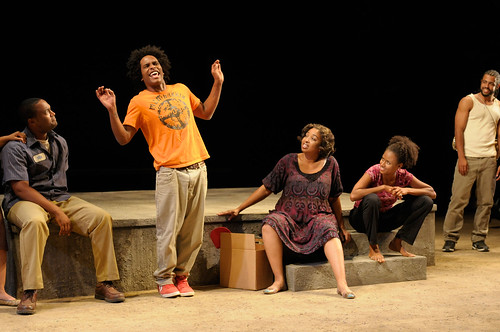

Cheryl Lynn Bruce is Shelah and Michael A. Shepperd is Creaker in Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Head of Passes on Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Thrust Stage. Below: Shepperd’s Creaker prepares for a party with his son, Crier (Jonathan Burke). Photos courtesy of kevinberne.com

Some houses leak when it rains. For Shelah, the deluge inside is almost as severe as the one outside, and that’s just the water. The metaphorical flood – of tragedy – has only just begun.

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Head of Passes, a co-production of Berkeley Repertory Theatre and New York’s Public Theater, takes its cue from Job, the world’s most famous sufferer and faith questioner. This time out, the one who will pray on bended knee and shake her fist at God is Shelah, the matriarch of a family whose Louisiana home sits where three forks of the Mississippi River come together in a wetlands area known as Head of Passes.

McCraney, a fast-rising playwright best known in the Bay Area for his extraordinary Brother/Sister Plays, is the kind of writer who blends real-world storytelling with elements of poetry and spirit to create a heightened theatrical language that conjures a world that looks and often feels like our own but then expands or contracts to feel epic or microscopic depending on the dramatic situation.

McCraney has a true gift, and it’s thrilling to fall into one of his plays. Head of Passes is an immersive experience in every way. The story McCraney unspools begins in the realm of classic American family drama – it feels like rich territory trod by O’Neill, Miller, Wilson and the like – but then becomes wholly McCraney in Act 2 when Shelah must deal with the wrath of God. Director Tina Landau (whodirected the play’s 2013 world premiere at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company) also delivers an astonishing physical production that drowns Berkeley Rep’s Thrust Stage in rain, flood and rising tides.

At first glance, G.W. Skip Mercier’s set reveals a large, handsome two-story home where there’s about to be a birthday party for Shelah, a widow, attended by close friends and her grown children. Festival lights have been strung in what looks to be a nicely appointed day room, where the party will take place. When the storm arrives, we see the rain outside the living room window, but soon enough, the leaky roof might as well not even be there. It’s raining in the living room, and no bucket or pile of towels will catch the overflow.

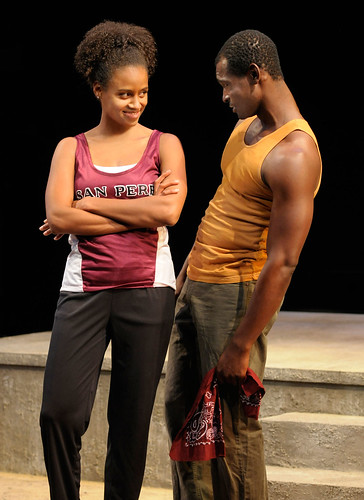

The party, as they say, must go on. Shelah (Cheryl Lynn Bruce, reprising the role from the Chicago premiere), doesn’t even remember it’s her birthday. She’s happy to see her sons Aubrey (Francois Battiste) and Spencer (Brian Tyree Henry) and daughter Cookie (Nikkole Salter), but she doesn’t want a fuss. She’s especially dismayed to see her doctor (James Carpenter, who gets one of the evening’s best laughs), the only other person who knows the truth about her precarious health.

Along with a candle-laden cake, the party offers up its fair share of drama, much of it centered around Shelah’s late husband and his relationship with his children (especially Cookie). There’s also a minor father-son drama involving Creaker (Michael A. Shepperd), Shelah’s major domo, and his son, Crier (Jonathan Burke), who seems only a few auditions away from landing a Broadway national tour.

By the end of Act 1, long-suppressed truths have been revealed, betrayals have occurred and relationships have fractured. The emotional storm is matched by the one outside, and havoc is wreaked so effectively, the technical prowess of the production threatens to overwhelm the plot.

But McCraney and Landau are too canny to let that happen. Act 2 essentially becomes a monologue for Shelah, a churchgoing woman all her life, who suffers wave after wave of bad news while the building over her head continuously threatens to dump her into the rising waters below.

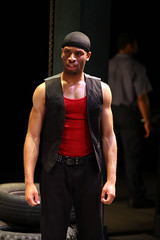

Bruce’s performance as Shelah feels appropriately matriarchal at first: she is what holds this family together, and her faith is easy. When she sees a handsome angel (Sullivan Jones), she knows what he’s there for, and she nervously but almost joyfully gives herself over to him so she can finally thank God herself. But it’s not going to be all harps and glowing lights for Shelah. If she thinks she has known suffering, she hasn’t seen anything yet.

Shelah’s agony is palpable, and Bruce’s ability to vacillate between anger and soul-crushing pain is remarkable. Of course there are no easy answers here. Faith is all about uncertainty, and that’s what Shelah has to wrestle with. She hasn’t always done the right thing or the good thing, and in this time of greatest need, she feels every misstep. Where her relationship with God yielded comfort, it now brings torment. Not even her closest friend (Kimberly Scott as Mae) can get close without Shelah lashing out. Her pain is practically toxic.

Shelah’s is a house that will not stand, though Head of Passes will long stand in memory as a powerful piece of American drama.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Head of Passes continues through May 24 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Thrust Stage, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $29 to $79. Call 510-647-2949 or visit www.berkeleyrep.org.