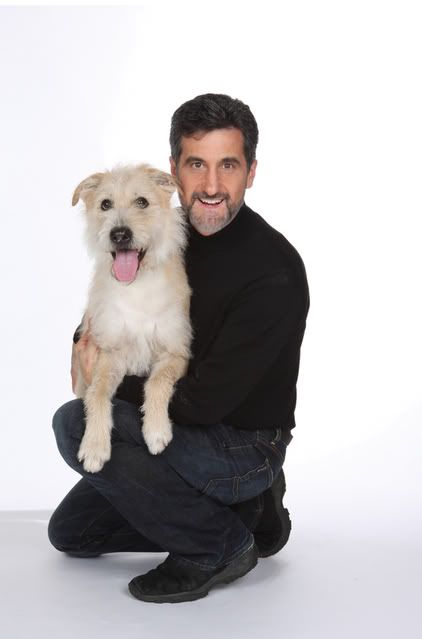

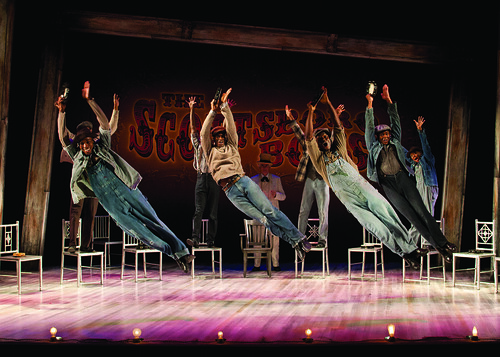

The amazing cast of The Scottsboro Boys in flight: (foreground, from left) David Bazemore as Olen Montgomery, Eric Jackson as Clarence Norris, James T. Lane as Ozie Powell and Shavey Brown as Willie Roberson. Below: Clifton Duncan is Haywood Patterson in the Kander and Ebb musical with a book by David Thompson and choreography and direction by Susan Stroman. Photos by Henry DiRocco

The Scottsboro Boys is a musical on crusade. Not for the first time in their storied career, composers John Kander and the late Fred Ebb make some of the worst human traits entertaining all the while championing the underdog and giving splendid voice to those who might be otherwise ignored or forgotten.

The crusade at hand is two-fold: Kander and Ebb, working with book writer David Thompson and choreographer/director Susan Stroman – a copacetic dream team if ever there was one – want to rescue the victims of a particularly ignominious chapter in American history from obscurity. And they want nothing short of exposing the roots of the Civil Rights Movement. They accomplish both goals, and The Scottsboro Boys is as powerful as it is entertaining, and that’s saying a lot on both counts.

The show concludes the season at American Conservatory Theater.

We’ve seen Kander and Ebb working this particular vein before: politics, horror, victimization and good, old razzle-dazzle. We saw it in Cabaret, where singing Nazis made the blood run cold; we saw it in Chicago, where cynicism and celebrity trumped humanity; we saw it in Kiss of the Spider Woman, where revolutionary zeal was squashed but the human spirit is not. This is not to say that Scottsboro is a re-tread in any way. There are echoes of other shows, other songs, but this compact, deeply felt show ratchets up the disturbance factor with its very form.

When the cast assembles for the opening number, “Hey, Hey, Hey, Hey!,” we are treated to an old-fashioned minstrel show. The set by Beowulf Boritt couldn’t be much simpler: three proscenium arches, slightly askew, and 13 chairs are the basic set-up for every scene, with a few moments of flash here and there. The difference with this minstrel show, even though it has a traditional host, or Interlocutor as he’s called (played by Broadway and TV veteran Hal Linden looking just like Col. Sanders), is that instead of white guys in black face, we have 11 African-American men putting on that disconcertingly cheerful display of minstrelsy. There are even the two traditional minstrel clowns: Mr. Tambo (JC Montgomery) and Mr. Bones (Jared Joseph) hamming it up and telling hoary old jokes. Under the sheen of jazz-handy, Al Jolson-y entertainment is something unsettling.

Perhaps it’s the none-too-subtle woman (the graceful C. Kelly Wright a former staple of the Bay Area theater scene) wandering silently around the stage who turns out to be a whisper from the future about to turn into a scream. Or perhaps it’s the jolly score, almost too jolly. The number “Commencing in Chattanooga” is a dazzling display of Stroman’s choreography as the cast turns those chairs into a train full of hobos circa 1931. But that good cheer quickly turns sour as the black strangers riding that train are accused of fighting with white men and raping two white women. The nine young men, who came to be known as the Scottsboro Boys because Scottsboro, Alabama happened to be where the train was stopped, were imprisoned and, over the course of many years, tried nine times and found guilty every time.

These incessant miscarriages of justice became a cause celebre for Northern agitators, personified by Jewish New York lawyer Samuel Liebowitz (played by Montgomery), who tried – and failed – to get the boys something resembling a fair trial, even after one of the women recanted her accusation.

It’s easy to see why this frustrating, demeaning, infuriating story captured the attention of Kander, Ebb, Stroman and Thompson, but it’s less easy to see why the story needed to be a musical. That’s where the notion of deconstructing the minstrel show – using a racist form of entertainment to tell a story of racism until basic humanity trumps race and storytelling – becomes incredibly potent. Kander and Ebb have a great time playing with minstrel sounds – think “Mammy” meets “Swanee” by way of “All That Jazz” – and the old-timey folk sound of the South (“Southern Days” lulls you then chills you to the bone). They are masters at couching horror in aggressively peppy, in-your-face entertainment. For proof, look no further than the shocking electric chair tap dance in which white prison guards attempt to scare the youngest of the boys, 12-year-old Eugene Williams (Nile Bullock) by electrocuting his pet frog in the electric chair.

If Chicago is a zesty lark with an impeccably choreographed wagging finger, The Scottsboro Boys is a deadly serious attempt (also impeccably choreographed) to make artistic amends for the ruin of nine lives, indeed any life, scarred by racism and/or mob stupidity (that’s a lot of lives). When the excellent Clifton Duncan as Heywood Patterson, the de facto leader of the boys, sings the anthemic “You Can’t Do Me,” all pretense of minstrel show has fallen away (though there remains one big minstrel punch). It’s a plea for human dignity and Heywood’s favorite subject, the truth.

This is challenging theater that often looks and sounds like it should be easy breezy. But this is Kander and Ebb, masters of moving musical theater forward in uncomfortable but ever-delightful ways. It’s a particular and tricky sort of genius, but genius none the less.

[bonus interviews]

Read my interview with John Kander and Susan Stroman for the San Francisco Chronicle here.

Read my interview with David Thompson for Theater Dogs here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Kander and Ebb’s The Scottsboro Boys continues through July 22 at American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $20-$95 (subject to change). Call 415-749-22228 or visit www.act-sf.org.

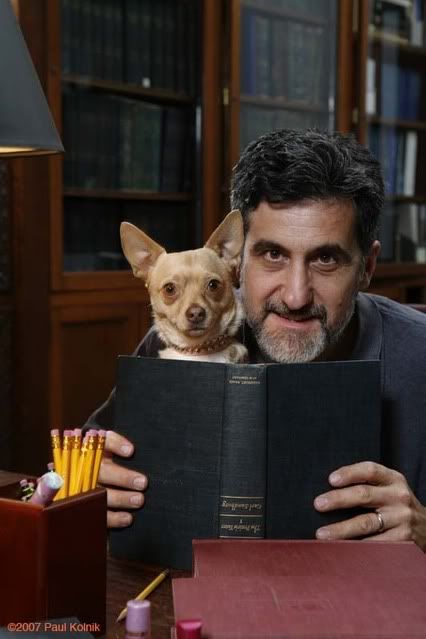

That was the original Sandy, who sat alongside Andrea McArdle as she warbled “Tomorrow” to the rafters. Berloni and the dog bonded in a big way. But the show was a flop, so when it was over, Berloni and his dog Sandy moved to Greenwich Village, and Berloni began studying with Stella Adler.

That was the original Sandy, who sat alongside Andrea McArdle as she warbled “Tomorrow” to the rafters. Berloni and the dog bonded in a big way. But the show was a flop, so when it was over, Berloni and his dog Sandy moved to Greenwich Village, and Berloni began studying with Stella Adler.