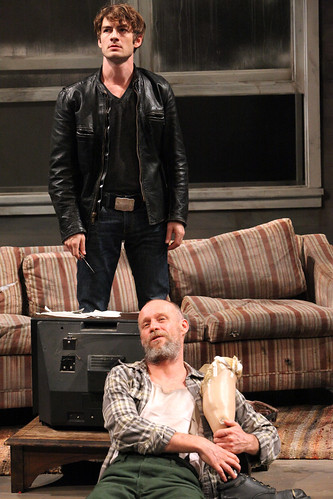

Chef Harry (Brian Dykstra, left) and server Rodney (Larry Powell) get ready for a big night at the restaurant in the world premiere of Theresa Rebeck’s Seared at San Francisco Playhouse. Below: Harry and Emily (Alex Sunderhaus), a consultant, argue over the future of the restaurant. Photos by Jessica Palopoli

I’m going to spoil something right off the bat about Theresa Rebeck’s fantastic new play Seared now receiving its world premiere from San Francisco Playhouse: there is no conventional romance. Just because the cast consists of one woman and three men does not mean there’s going to be a burgeoning love story or a sordid triangle or break-ups or make-ups. No, the central love story comes out of a friendship and business partnership between a chef and a money guy who open a small restaurant in Brooklyn.

This is a workplace story, and though it’s set entirely in the kitchen of the restaurant, it hits on big themes about that tricky intersection between artistic integrity and sustainable commercial success. The artist in this case is chef Harry (the superb and entirely believable Brian Dykstra), a genius behind the stove whose superb work fills the restaurant’s 16 settings every night and has started to garner the attention of the wider world. With a recent favorable mention in New York magazine, Harry’s partner, Mike (the ever-reliable and ever-wonderful Rod Gnapp) has brought in a consultant, Emily (a pitch-perfect Alex Sunderhaus), to save the little eatery from imminent demise.

Emily and Harry clash, but then again Harry clashes with just about everybody because that’s what he does. Everything is a fight with him except his interactions with the restaurant’s sole employee, server Rodney (an excellent Larry Powell), whose relaxed humor diffuses tension while masking his deep devotion to Harry and his own culinary skills.

The world that Rebeck creates in the Playhouse commission is incredibly real, and not just because the fully functional set by Bill English is so convincing you half expect the dishes created up there to be passed around to salivating audience members. Rebeck’s world is fueled by ego and friendship and complicated interactions that are both volatile and tender, funny and deeply angry, and that’s a world that bears watching for more than two hours.

Rebeck’s play, flawlessly directed by Margarett Perry, is so involving that at a certain point in this darkly funny, deliciously detailed drama you expect an overheated audience member to stand up and shout something along the lines of, “Just cook the fucking scallops already!” While disruptive and inappropriate, that would also mark a triumph for Rebeck and her cast and creative team. Never has the creation of a seafood dish fueled such dramatic agony and tension. There’s really not much plot here – a struggling restaurant attempts to get into the black – but everything feels huge and important, a stovetop epic if you will, and it’s thrilling.

It’s that much easier to fall into this world because it is so perfectly and convincingly created. Of course English’s set helps (as do Robert Hand’s lights and Theodore J.J. Hulsker’s sound design), but Dykstra is thoroughly convincing has he chops and sautés and sauces with real knives and real flame. He has to act (powerfully) while not drawing blood or creating blisters or accidentally stabbing a costar. He does it all with such aplomb that our focus happily rests on the characters and their interactions.

When Dykstra’s Harry goes off on something (“No takers for the lamb – I hate the 21st century”), it’s like verbal fireworks. The thought of a $3 donut triggers one such speech, and to hear him talk about the wonder of butter is an epicurean/existential delight. He also rants about the artificiality of money (“the biggest lie ever perpetrated”) vs. the reality of food to great effect. But Harry’s not the only one with great moments. All the characters get them, even Emily, the seemingly slick consultant whose use of the words “amazing” and “impeccable” could inspire a drinking game. She goes off on Harry in an artist vs. asshole with talent rant that includes the zinger, “Every reasonably talented white man has been told he’s a genius.” Ouch. And hooray.

Seared turns out to be not unlike the dishes its chef creates: artfully made, crafted with the best possible ingredients and served with confident flair. That it’s so delicious and deeply satisfying makes it the haute cuisine of contemporary drama.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Theresa Rebeck’s Seared continues through Nov. 12 at San Francisco Playhouse, 450 Post St., San Francisco. Tickets are $20-$125. Call 415-677-9596 or visit www.sfplayhouse.org.