Writing about his high school experience proved therapeutic for playwright Itamar Moses, a Berkeley native whose Yellowjackets has its world premiere this week at Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

The 30-year-old writer headed back to the year 1994 to dramatically reconstruct his junior year at Berkeley High School, when he was editor of the school newspaper, The Jacket, and racial tensions were dividing the student body.

The 30-year-old writer headed back to the year 1994 to dramatically reconstruct his junior year at Berkeley High School, when he was editor of the school newspaper, The Jacket, and racial tensions were dividing the student body.

“High school is a potent time,” Moses says one morning before a rehearsal. “I try to examine why that is on this canvas. I was able to work out specific feelings here, and it’s amazing to me to discover that I did have a different perspective. I had such firm beliefs at the time, but I could actually see a more complex, multiplicity of viewpoints I didn’t have at the time. Things seemed so obvious to me as a student who was feeling threatened or getting messed with. I always hoped I’d see a larger perspective. I’m amazed I actually did.”

Moses, who now lives in Brooklyn’s Park Slope area, says that even though he was re-creating experiences of 14 years ago, he could hear the voices clearly.

“I feel like I still talk like I did in high school,” Moses says and laughs. “The other voices in the play, the ones that aren’t mine, I’ve been hearing for years. As opposed to just crafting dialogue, I tried to hear it. I have voices in there” – he points to his head – “not in a mental health way, but in a historical way.”

Some of those voices belong to African-American and Latino characters, which required Moses to write outside his race.

“Sure, there was an element of fear of fraudulence,” he says. “I did feel an internal hurdle. Am I entitled to do this? Is this OK? Solution was to remind myself that my choices were to do it or not write about Berkeley High at all. Usually that’s how to get yourself to do something difficult: get to the point where there’s no alternative. I guess I have the same feeling about writing female characters. In a weird way, you let go of the idea you’re writing from the outside in. Characters have to come from the inside out or they’ll play that way on stage. Every character is a fragment of your psyche, no matter the race or gender.”

Like most writers who are writing about a specific time in their lives, Moses takes the fictional route. For instance, he says he’s most like Avi, the new editor of the newspaper who is dealing with a faculty boycotting his paper. But he’s also like Trevor, the newspaper staff member who is getting bullied in a pretty serious way.

“I wanted to get both experiences in there,” Moses says. “But neither character is fully me. The question of what’s autobiographical and what’s not is complicated. There are elements of truth in the fiction.”

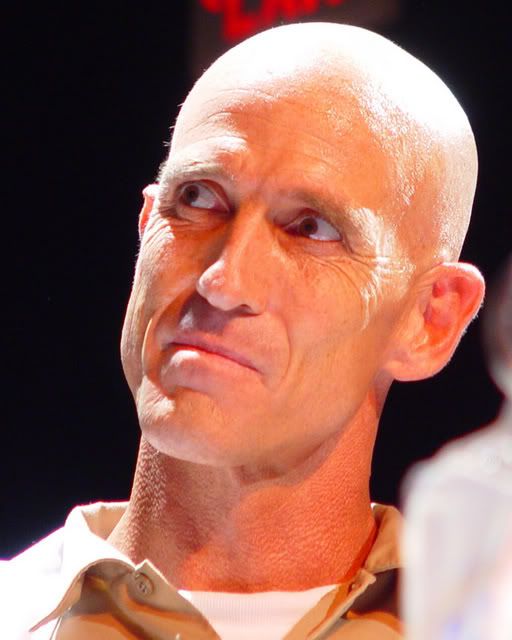

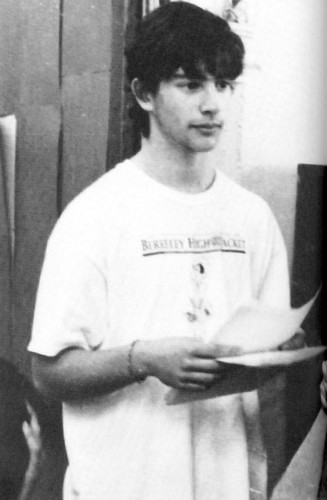

Moses (in a photo from his high school yearbook at right, not the Jacket T-shirt) joined the school newspaper staff in his freshman year and has been writing since (he was also a humor columnist for the Yale Daily News in his college years). But the writer says he’s still not sure if writing is “his thing.”

Moses (in a photo from his high school yearbook at right, not the Jacket T-shirt) joined the school newspaper staff in his freshman year and has been writing since (he was also a humor columnist for the Yale Daily News in his college years). But the writer says he’s still not sure if writing is “his thing.”

“When I was 9 or 10, I read a lot of sci-fi/fantasy. It was an obsession. I thought I’d write that. My initial plan was to be Piers Anthony or Susan Cooper or whoever. I got to Berkeley High, and I don’t know why, but I was attracted to the newspaper. I can’t remember how I made that decision. I liked it a lot. I knew it was my big high school extracurricular activity. Never planned to be a journalist.”

Then, in college, theater became his extracurricular activity, and now he’s a playwright in demand (his biggest hit, Bach at Leipzig, recently had its area premiere at Shakespeare Santa Cruz).

Working on Yellowjackets for the last two years, Moses was approached by a TV network – he says it shall remain nameless – about turning the play into a TV series. Unlike the play, which allows the young actors to play the adults as well as the students, the TV geniuses wanted to focus primarily on the adults.

“To me, the play is interesting because it focuses on the kids,” Moses says. “That’s what makes it a microcosm. For the purposes of TV, they may be right. But on stage, kids playing adults was the obvious choice.”

More than a decade away from his high school experience, Moses says maturity isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

“If anything, I feel less clarity and less direct passion and less vibrating sense of the electricity of possibility of the world than I did when I was a teenager,” he says. “When I was in graduate school, Tony Kushner spoke to us, and the thing he said that I remember most vividly was that maturity in our culture is defined as the ability not to feel too strongly about anything. If you buy into that, especially as an artist, you’re screwed because it means you’re deadened. As writers, he said, be careful not to be embarrassed by the extremities of feeling. Certainly how much you want that in your life and relationships is a question, but you definitely want in your work. In Yellowjackets, taking the kids seriously, focusing on them was a way to do that…to write about characters whose id is louder than their superego.”

Moses will take part in a free “Page to Stage” talk on Berkeley Rep’s Thrust Stage at 7 p.m. Sept. 22.

Yellowjackets continues through Oct. 12 at the Thrust Stage, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $33-$71. Call 510-647-2949 or visit www.berkeleyrep.org.

At readings of the play, whether in Berkeley or in the nation’s capital, audiences are responding and sticking around for the post-show discussion.

At readings of the play, whether in Berkeley or in the nation’s capital, audiences are responding and sticking around for the post-show discussion. On the evolution of hip-hop theater: “Hip-hop is such a loaded word, loaded with the wrong cultural references because of mainstream commercial culture. A lot of times, hip-hop theater is perceived by regional or nonprofit or for-profit theater world as a novelty. Or as music. People expect breakdancers to come out. It’s unfortunate because what’s happening in the meantime is that this entire dialogue, this language and canon from the hip-hop generation is being ignored. My fear is that the stories of the hip-hop generation — forget the breakdancers and rappers — is not going to be popular until 500 years from now. That’s unfortunate because these stories are immediate and urgent and necessary. When the stories are embraced, they’re embraced as a novelty or a one-shot deal, not as a movement, a genre or a generational niche or aesthetic. They fill the color slot for the season. Or this is the show to write the grant to get the young audience in. It’s that black and white. It really is.”

On the evolution of hip-hop theater: “Hip-hop is such a loaded word, loaded with the wrong cultural references because of mainstream commercial culture. A lot of times, hip-hop theater is perceived by regional or nonprofit or for-profit theater world as a novelty. Or as music. People expect breakdancers to come out. It’s unfortunate because what’s happening in the meantime is that this entire dialogue, this language and canon from the hip-hop generation is being ignored. My fear is that the stories of the hip-hop generation — forget the breakdancers and rappers — is not going to be popular until 500 years from now. That’s unfortunate because these stories are immediate and urgent and necessary. When the stories are embraced, they’re embraced as a novelty or a one-shot deal, not as a movement, a genre or a generational niche or aesthetic. They fill the color slot for the season. Or this is the show to write the grant to get the young audience in. It’s that black and white. It really is.”

On going back to Czechoslovakia after the fall of Communism: “I had never been back to my birthplace. My mother had died five years earlier, and her death released me, gave me permission to go. While she lived she didn’t want to look back. There’s so much I didn’t know about her and her family. It was ignorance I was happy to live in. I didn’t care to invigilate my mother.”

On going back to Czechoslovakia after the fall of Communism: “I had never been back to my birthplace. My mother had died five years earlier, and her death released me, gave me permission to go. While she lived she didn’t want to look back. There’s so much I didn’t know about her and her family. It was ignorance I was happy to live in. I didn’t care to invigilate my mother.”