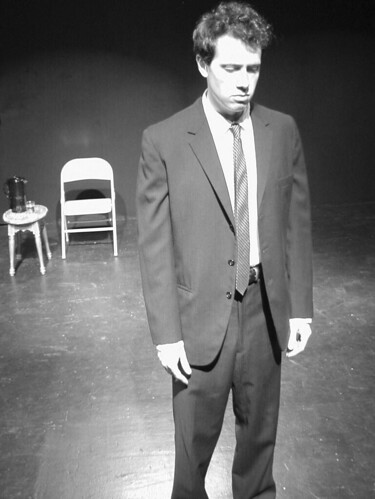

The cast of Rinne Groff’s 77%, part of San Francisco Playhouse’s Sandbox Series for new play development: (from left) Arwen Anderson, Karen Grassle, Patrick Russell. Below: Russell’s Eric shares a drink and some bonding with his mother-in-law, Frankie (Grassle). Photos by Fei Cai

The title of Rinne Groff’s new play 77% may seem cold and statistical, but it’s actually wonderfully charming. You have to see the play to get it, but here’s something to know: if you can achieve that percentage with a romantic partner of some kind, you’re doing a really good job.

A play about marriage, among other things, 77% receives its world premiere as part of San Francisco Playhouse’s Sandbox Series for new plays. It’s a remarkable play, in part, because it seems so unremarkable. The set-up smacks of sitcom fodder: he’s a stay-at-home dad/children’s book illustrator, she’s a high-powered businesswoman who travels a lot for work and her mom is currently living with them and helping with the kids. She’s always dreamed of having three children, but to add one more kid to their brood will require the assistance of medical science and the wonders of in-vitro fertilization.

On an extremely simple set – a few chairs, a table on wheels and an abstract backdrop that looks like a sailboat’s sail – this fast-paced comedy/drama plays out in 80 minutes but still manages to feel substantial.

Credit Groff’s sharp script, which cuts through a whole lot of layers to get to the good stuff in a hurry, and director Marissa Wolf’s stellar work with a crack trio of actors for managing a tricky blend of speed and naturalism. The rhythms are from real life, but there’s a theatrical push to the short scenes that infuses them with an irresistible electrical charge.

This is apparent in the first scene, as Eric (Patrick Russell) and Melissa (Arwen Anderson) are taking a drive in their new minivan. Melissa has returned from a work trip, and the following day, they resume their IVF treatments in hopes of a third child. Melissa is driving, and it’s clear that though these spouses are thoroughly and deeply connected, there’s all kinds of tension. Part of that is from her being the breadwinner. Eric is sensitive about the way Melissa talks about his work or about his daily life with the kids. In Groff’s deft hands, this scene is less about a challenged macho ego and much more about how people – especially those in what would be considered non-traditional roles – connect to their self-worth.

Anderson and Russell are so natural in their roles, it’s easy to go on this ride with them. They scuffle, they laugh, they sext (hilariously and not without a frisson of super sexiness). Life is difficult for them, but tension and conflict is part of the landscape and not the deal breaker it tends to be in less sophisticated work.

Adding to the mix of complication is Karen Grassle as Frankie, Melissa’s mom. She’s staying with her daughter’s family while her husband is on a solo sailing trip (he’s delivering a sloop, and much is made of the word “sloop”). There’s a fair percentage (not 77%) of the play that is about a strained mother-daughter relationship without that ever seeming to be at the fore. Both mother and daughter sit in heavy judgement of each other, but on a slightly drunken evening when Eric and Frankie bond, we find out a whole lot more about who Frankie is (and, by the way, who Eric is), and it’s fantastic. We sense a through line from mother to daughter and even to father, who is only ever acknowledged as a faint image on a FaceTime call.

SF Playhouse’s Sandbox Series, as it did last year with Aaron Loeb’s, Ideation, which made its way to the company’s main stage this season (read my review here) takes a simple approach to new work. Hand the work to skilled directors and actors and let the script shine through a straightforward, no-frills production. Sometimes that’s the best possible way to experience a play. With a play as smart, funny and incisive as 77%, it’s not hard to imagine many more productions of the play in the near future. Odds are 100 percent hit.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Rinne Groff’s 77% continues through Nov. 22 at the Tides Theater, 533 Sutter St., San Francisco, a presentation of San Francisco Playhouse’s Sandbox Series. Tickets are $20. Call 415-677-9596 or visit www.sfplayhouse.org.