EXTENDED THROUGH APRIL 3!

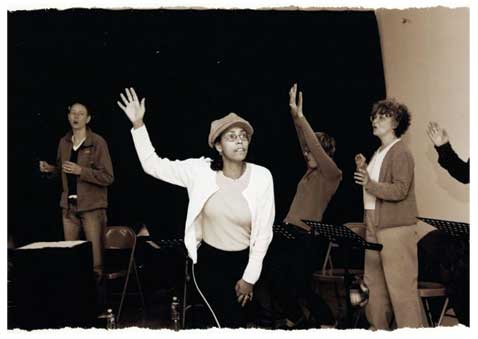

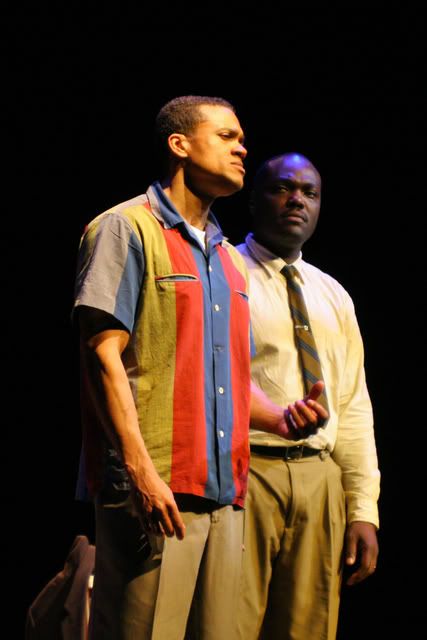

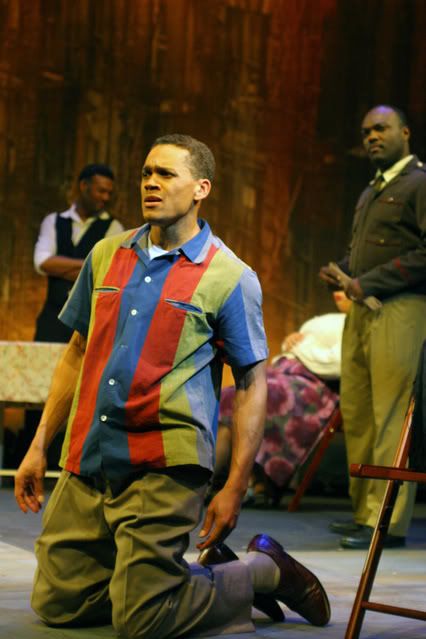

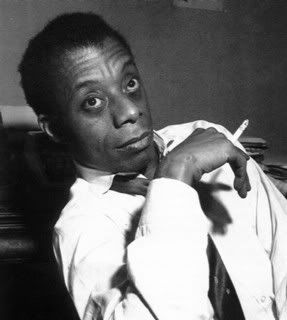

Pictured from left: Daveed Diggs, Traci Tolmaire, Margo Hall and Dwight Huntsman in the world premiere

of Chinaka Hodge’s Mirrors in Every Corner at Intersection for the Arts. Photos by Pak Han

Watching the audience on stage at Intersection for the Arts was a stunning experience. Sometimes theater companies trying to push boundaries and break down walls really do get it right.

The show in this case is Oakland playwright Chinaka Hodge’sMirrors in Every Corner, and the companies involved in bringing it to life are many: Intersection, Campo Santo and The Living Word Project’sYouth Speaks theater company. They say it can take a village. In this case, it takes a community.

When you walk into the performance space at Intersection – sort of a bunker-like lecture hall – there’s something definitely different going on. The audience is milling about the stage as if at an art gallery. Wait – the stage is an art gallery. When artist Evan Bissell was asked to collaborate on the show and create a set, he didn’t quite know how to go about doing that, so he created a stunning art installation about families and racial identity and about community. There’s a giant mural of a Mission District family across the back wall, while on another there are seemingly hundreds of framed photos, collages, stories and poems all created by families in the Mission who came to Intersection for what turned out to be a hugely successful free family portrait day. Some came back to create art and write poems.

Intersection has always been a wall breaker, even if only because you have to cross the stage to get to the bathroom. The audience has always seemed part of the action, but this installation takes the concept even further.

By the time Hodge’s play begins, the audience is in an open-minded space ready to experience more art, and Hodge delivers in a big way. Her play – directed by Marc Bamuthi Joseph – is hilarious and deadly serious, outlandish and completely personal. She may only be 25 (and a product of the Youth Speaks program since her mid-teens), but this is a playwright to watch.

She tells the story of a black Oakland family with a secret. A mom (Margo Hall) and her three boys (Daveed Diggs, Dwight Huntsman and Traci Tolmaire) play cards and flip back and forth through time to tell the story of the family’s youngest member, Miranda aka “Random,” who for some mysterious reason was born white.

What that means to the family, let alone to the outside world, fills the play’s 80-some minutes with familiar warmth and humor, intense soul search and surprising violence. Hodge firmly grounds her play in a traditional family story, but she plays with all kinds of flourishes (some that work better than others) that imbue every moment with the tension of surprise and the delight of seeing a playwright flower.

As the matriarch, Hall is an intelligent woman caught up in a biological mystery. Hall also plays Random, and it is a testament to this actor’s tremendous skill that much of the play’s excitement comes from watching her slip effortlessly from role to role.

All the actors are terrific, but Diggs is especially vivid as Watts, the eldest child and the one with the wryest, driest sense of humor.

Mirrors in Every Corner reflects all kinds of wonderful things, most notably a young playwright making a sensational debut and a theatrical collaboration that doesn’t just talk about change but makes it.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Chinaka Hodge’s Mirrors in Every Corner continues an extended run through March 28 at Intersection for the Arts, 446 Valencia St., San Francisco. Tickets are $15-$25. Call 415 626-2787 ext. 09 or visit www.theintersection.org.

Hall’s production is first rate. Her ensemble, which also includes Mujahid Abdul-Rashid and Robert Hampton, is fluid and capable of playing anything from a small child (Hampton) to a fireplug of a jazz player (Robinson).

Hall’s production is first rate. Her ensemble, which also includes Mujahid Abdul-Rashid and Robert Hampton, is fluid and capable of playing anything from a small child (Hampton) to a fireplug of a jazz player (Robinson).

Baldwin’s story, published in 1957 and collected in the 1965 book, Going to Meet the Man, follows two brothers in 1950s Harlem. One is a schoolteacher and family man. The other is a jazz pianist with a troubled past.

Baldwin’s story, published in 1957 and collected in the 1965 book, Going to Meet the Man, follows two brothers in 1950s Harlem. One is a schoolteacher and family man. The other is a jazz pianist with a troubled past.