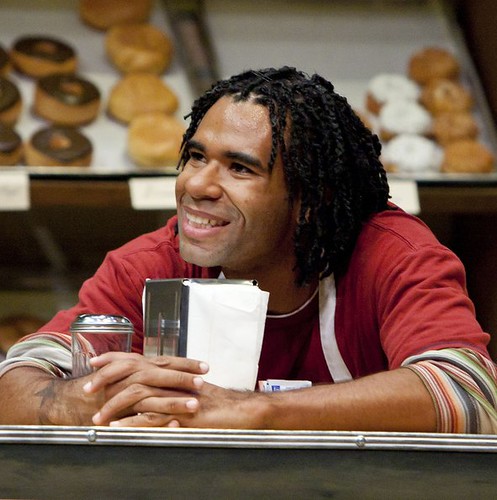

The cast of Aurora Theatre Company’s Widowers’ Houses by George Bernard Shaw includes (from left) Megan Trout as Blanche Sartorius, Dan Hoyle as Harry Trench, Michael Gene Sullivan as Cokane and Warren David Keith as Mr. Sartorius. Below: Keith’s Sartorius (left) wrangles with Howard Swain’s Lickcheese. Photos by David Allen

George Bernard Shaw’s Widowers’ Houses last played Berkeley’s Aurora Theatre Company more than 20 years ago, and though the theater company has come up on the world (bigger, spiffier theater), the satirical world of Shaw’s play still reflects badly on our own lack of evolution where greed, poverty and decency are concerned.

That 1997 production, directed by Aurora co-founder, the late Barbara Oliver, made me a fan of Shaw’s first produced play and made me an immediate fan of Aurora’s chamber approach to great plays where every subtlety and nuance is amplified and the intimacy increases your connection to the characters and the action.

The new production of Widowers’ Houses, directed by the estimable Joy Carlin, is certainly handsome to look at, from the giant gold-framed screen depicting Victorian life dominating the set by Kent Dorsey, who also did the lighting design, to the posh costumes by Callie Floor (who also makes shabby costumes look so real you can practically smell them).

Dispensing with three acts in under 2 1/2 hours, Carlin’s pace is brisk but not rushed. There’s a surprising disparity in the small six-person cast. There’s the expected precision and excellence bringing shaw to vibrant life, but then there’s also some distracting hamminess and amateurishness that keeps the play from truly taking off.

But what’s good is really good. Warren David Keith is the dark heart of the play as Sartorius, a self-made man of means who turns out to be one of London’s biggest slumlords. He swears he does it all for his daughter, Blanche (an incisive Megan Trout), whom he has raised on his own (and turned into a spoiled, tiny-hearted brat in the process). He is also of the opinion that there’s nothing to be done with the poor except leave them to their own wretched devices. If you extend any sort of generosity – like repairing a dangerous bannister, for instance – they’ll just turn it into so much firewood. You might as well take what you can from them and keep moving along.

Keith is cold and imperious as well as frustratingly smart and considered. His Sartorius is commanding and chilling. He speaks from the heart, but where his heart ought to be is a giant bag of cold coins.

Equally good is Howard Swain as Lickcheese, whose Dickensian name is so very appropriate. He’s Sartorius’ henchman who wrings every last cent from the tenants, many of whom are paying for a quarter of a room. Lickcheese also swears he carries out his heinous duties to support his own family, but he clearly relishes it. When Lickcheese returns later in the play a changed man, he calls to mind a later Shaw character, Alfred P. Doolittle in Pygmalion, who will also use his life on the streets as the basis for a future fortune.

Trout’s Blanche is a delicious character – a prissy Victorian lady hoping to woo marry a naive young doctor she and her father met in their European travels but who reveals herself to be vicious in her thinking and her actions. She hates the poor almost as much as she hates her maid, whom she beats and berates incessantly (the maid is played by a broadly comic Sarah Mitchell). Blanche is the very opposite of what you think of when you think of a Victorian lady in that she is robustly physical and has no qualms in speaking her mind.

By the third act, Shaw’s stomping on his soapbox results in splinters more than barbs, but his point is well made: one man’s riches is the result of another’s poverty. Advantage will always be taken, and even the most noble among us are culpable, whether we realize it or not, in keeping this system alive and thriving. In other words, the play could have been written last week. When the Aurora produces Widowers’ Houses again in another 20 years or so, if the world still exists, the same will undoubtedly remain true.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

George Bernard Shaw’s Widowers’ Houses continues through March 4 at Aurora Theatre Company, 2081 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $33-$65. Call 510-843-4822 or visit www.auroratheatre.org.