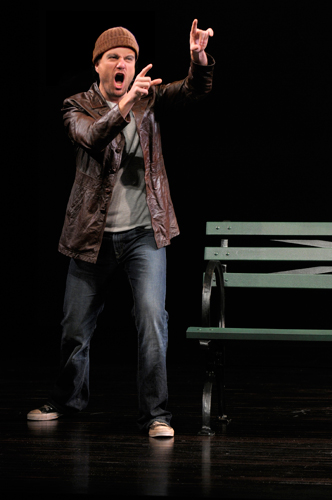

Nancy (Ellen McLaughlin) and Charlie (James Carpenter) meet Leslie (Seann Gallagher), a human-sized lizard that has just crawled out of the sea, in Edward Albee’s Seascape at ACT’s Geary Theater through Feb. 17. Below: McLaughlin and Carpenter are startled by two human-sized lizards, played by Gallagher and Sarah Nina Hayon. Photos by Kevin Berne

As directing debuts go, Pam MacKinnon’s for American Conservatory Theater is pretty auspicious. Her production of Seascape by Edward Albee is her first on the Geary Theater stage since taking over as artistic director last year. A Tony Award-winner (for Albee’s 2012 revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) who has worked on other Bay Area stages (Berkeley Rep, Magic), MacKinnon seems to have landed quite comfortably in the world of institutional regional theater.

Her production of Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1975 play crackles with crisp performances that easily carry the audience through the more naturalistic aspects of the play and into its wilder, more absurdist regions. When the curtain rises, there’s a moment of refreshing awe at the sight of David Zinn’s set: tall, grassy sand dunes along the Atlantic coast. The sound of waves crash in the background, the peace occasionally interrupted by a screaming jet plane overhead (sound design by Brendan Aanes). It’s interesting that the back of the theater is left exposed, as are all the bright, sunny lights that comprise designer Isabella Byrd’s grid. There’s reality and there’s fantasy reality occupying the same space, which is entirely appropriate for this play.

Seascape begins as a marital drama (an Albee specialty). A long-married couple is readjusting to retirement and the twin notions of aging and mortality as reality rather than concept. Nancy (Ellen McLaughlin) has found her happy place on this sunny stretch of beach. She envisions a future free of grown children, grandchildren and responsibilities. She floats the notion of becoming beach nomads and seeing the world from sand strip to sand strip. But Charlie (James Carpenter) wants to do nothing. “We’ve earned a rest,” he keeps saying. This schism – “purgatory before purgatory” – is cause for a discussion that gets deeper and more intimate between husband and wife, and McLaughlin and Carpenter are riveting. They feel deeply connected yet strongly individual and can also be quite funny.

Traversing the bumpy landscape of matrimony with this couple makes for surprisingly grand entertainment. Nothing major or melodramatic is happening, but in a way, as they review their life together, everything is happening. But then something major really does happen: a couple of human-sized lizards crawl out of the sea and begin a fairly deep existential discussion with the humans (once everyone determines that one couple is not interested in eating the other). It’s a little like the two-couple dynamic of Virginia Woolf meets the monster-in-the-house horror of A Delicate Balance.

Because Albee’s script is so smart and funny, and because the performances of the humans and the lizards – Sarah Nina Hayon as Sarah and Seann Gallagher as Leslie – are so warm and real, there’s never any difficulty making the leap into fantasy. The absurdity is quite enjoyable (like the man having the affair with the goat named Sylvia in The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?), although Albee never quite solves the internal logic of how Sarah and Leslie have excellent vocabularies and seem to know what human months and years are but don’t know what birds are. Because we’re in the realm of evolution and those key moments when the next phase actually happens, it feels like something’s missing in the story of the lizards’ evolution up to this point. But we do get some wonderful “learning” moments, as when the lizards learn the human custom of shaking hands to say hello.

Designer Zinn’s costumes for Sarah and Leslie are spectacular, and the way Hayon and Gallagher inhabit them makes them so much more than green suits with giant tails. It’s easy to fall in love with these creatures, especially Sarah, who is curious and empathetic in ways that make you root for her personal evolution. If she can do it, you know Leslie, who seems not quite as advanced, can do it, too.

There’s a sag in Act 2, and Albee doesn’t quite seem to know where he wants his curious quartet to land. The overall tone of Seascape carries the tidal weight of existence and emotional turmoil, but that is lifted somehow by an element of hope and acceptance.

[BONUS INTERVIEW]

I talked to ACT’s new artistic director, Pam MacKinnon, about making her ACT directorial debut with Seascape for the San Francisco Chronicle. Read the story here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Edward Albee’s Seascape continues through Feb. 17 at American Conservatory Theater’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $15-$110 (subject to change). Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org.

Rock ‘n’ Roll by Tom Stoppard (Sept. 11-Oct. 12) — Surprising no one, especially after Stoppard’s visit to ACT in January, the West Coast premiere of this London and New York hit will be directed by ACT artistic director Carey Perloff. The drama, Stoppard’s most autobiographical, follows a Czech man in England drawn back to the fight against the Soviets in his native Prague — and it’s all set to a suitably rocky soundtrack full of the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd.

Rock ‘n’ Roll by Tom Stoppard (Sept. 11-Oct. 12) — Surprising no one, especially after Stoppard’s visit to ACT in January, the West Coast premiere of this London and New York hit will be directed by ACT artistic director Carey Perloff. The drama, Stoppard’s most autobiographical, follows a Czech man in England drawn back to the fight against the Soviets in his native Prague — and it’s all set to a suitably rocky soundtrack full of the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd. Souvenir: A Fantasia on the Life of Florence Foster Jenkins by Stephen Temperly (Feb. 13-March 15, 2009) — If you want a sneak peek at this off-kilter musical biography, head down to San Jose Repertory Theatre, where the regional premiere of Souvenir opens this week starring Patti Cohenour. The ACT production will star Judy Kaye, right, (Mrs. Lovett in the Sweeney Todd that stopped at ACT last fall), who was nominated for the role in 2006. She plays Jenkins, a New York socialite who fancied herself an opera diva though she could hardly carry a tune.

Souvenir: A Fantasia on the Life of Florence Foster Jenkins by Stephen Temperly (Feb. 13-March 15, 2009) — If you want a sneak peek at this off-kilter musical biography, head down to San Jose Repertory Theatre, where the regional premiere of Souvenir opens this week starring Patti Cohenour. The ACT production will star Judy Kaye, right, (Mrs. Lovett in the Sweeney Todd that stopped at ACT last fall), who was nominated for the role in 2006. She plays Jenkins, a New York socialite who fancied herself an opera diva though she could hardly carry a tune.