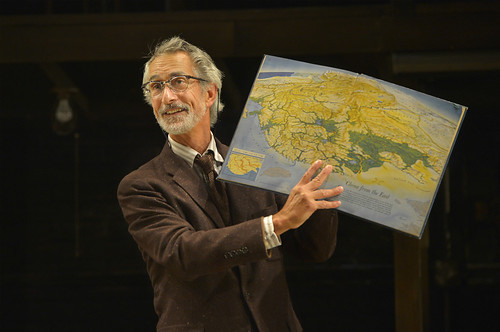

Recovering from devastating injuries in a Long Island hospital room, Chester Bailey (Dan Clegg, right) is visited by Dr. Philip Cotton (David Strathairn) in American Conservatory Theater’s world-premiere staging of Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey at the Strand Theater. Below: Bailey (left) and Cotton work through some serious issues of reality vs. imagination. Photos by Kevin Berne

In Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey, it’s reality vs. imagination, and the audience wins.

This world-premiere production from American Conservatory Theater is a modest two-hander performed in the intimate Strand Theater, an old-fashioned feeling play woven through with dry humor and compassion. Think of it sort of as an Oliver Sacks case history come to life with a modicum of theatrical flair.

I say a modicum because, for all intents and purposes, this could be a radio play, which seems fitting for a story set in 1945 and dealing with the effects of the World War II. The design elements – industrial girders and windows set by Nina Ball, sharp lighting by Robert Hand – are strong, but this is really an exercise in storytelling and listening to two characters, played by two appealing actors, figure each other out.

It takes a half an hour of the play’s 90 minutes for the two characters to actually be in the same room, but until then, we get their backstory. David Strathairn is Dr. Philip Cotton, who is working at a mental hospital in Long Island. Aside from personal details like his failed marriage and his affair with his boss’ wife, we learn that one of his most interesting patients is Chester Bailey, played by Dan Clegg, a Brooklyn man in his early 20s whose parents interfered to keep him out of the war by getting him a job in the naval shipyards. Their efforts to safeguard their only child backfired when Chester was involved in a terrible incident that robbed him of his sight and his hands. The thing is that Chester, teetering on that line between imagination and delusion, thinks he can see and thinks he still has two perfectly good hands.

Developed in New Strands, ACT’s new works program, Chester Bailey has the feel of a ghost story (Jo Stafford singing “Haunted Heart” as the lights come up sets just the right tone) because between the dueling narratives, we’re never quite sure what’s real and what’s not, and that’s good for the drama. Director Ron Lagomarsino effectively twines Chester and Dr. Cotton’s stories to the point that all of us – characters and audience – are hoping the ghosts are real.

Strathairn is such good company on stage. His Dr. Cotton is droll and wise and ultimately the kind of doctor we’d all wish for – he’s smart enough to know when to stop being a clinician and start being a human being. Clegg, once you get past his unconvincing Brooklyn accent, is an endearing, complicated Chester, a young man tormented by not serving his country and then abandoned through a series of misfortunes. It’s a tricky role because we have to like Chester and understand his submission to his parents, his denial surrounding his injuries and his rather remarkable ability to create and inhabit a reality so different from the one he’s living.

There’s nothing groundbreaking or particularly edgy in Chester Bailey. It’s an intriguing story, well told and warmth, intelligence and humor.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Joseph Dougherty’s Chester Bailey continues through June 12 at American Conservatory Theater’s Strand Theater, 1127 Market St., San Francisco. Tickets are $25 to $75 (subject to change). Call 415-749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org