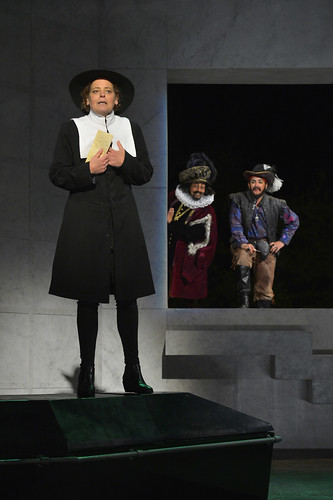

The cast of American Conservatory Theater’s Fefu and Her Friends by María Irene Fornés includes (from left) Lisa Anne Porter as Julia, Sarita Ocón as Christina, Jennifer Ikeda as Cindy, Cindy Goldfield as Emma, Catherine Castellanos as Fefu and Marga Gomez as Cecilia. BELOW: Taking place in various spots around The Strand, Fefu immerses its audience in scenes like this one in the lobby with Castellanos and Goldfield on a balcony. Photos by Kevin Berne.

There are actors in American Conservatory Theater’s Fefu and Her friends that I would travel continents to see. I would climb flights of stairs and even sit on the floor to get to see them perform. The good news about Fefu is that it’s not continents away – it’s down on Market Street in a Strand Theater that has been transformed, in its theatrical way, into a New England country home full of interesting people. You will, however, have to climb stairs (or take the elevator) and sit on the floor (if you want to) because this is an immersive production that takes you all over the building.

With its premiere in 1977, María Irene Fornés’ Fefu (pronounced FEH-foo) emerged as a theatrical experiment in feminism. Set in 1935 during a reunion of college friends, the all-women cast explores their relationships to each other and to a world that desperately wants men and women to conform to accepted gender roles.

There’s not a traditional plot, but that’s not really the point here. It’s all about discovery and play. We first meet the eight characters as they arrive at Fefu’s house for a weekend of fun and rehearsal for an upcoming charity event. The audience is seated in the theater, and the characters inhabit the lovely home designed by Tanya Orellana in a traditional proscenium setting. The tone that emerges under Pam MacKinnon’s direction is one of joviality, introspection and the ever-present possibility of surprise (good and bad).

For the second of the play’s three parts, the audience is separated into four groups (your color-coded wristband lets you know which group you’re in) and taken into various parts of Fefu’s house. Our group first headed to the lobby, which had been transformed into Fefu’s garden, complete with grass (of the artificial variety), gorgeous Monet-like projections (by Hana S. Kim) and a real-life plant exchange (bring a plant, take a plant, so if you’re going definitely bring a plant!). Fefu (Catherine Castellanos) and Emma (Cindy Goldfield) have an al fresco chat about, among other things, how none of us talks about our genitals enough.

Then we headed backstage into a dimly lit room (Russell H. Champa is responsible for the gorgeous lighting throughout the building), where Julia (a mesmerizing Lisa Anne Porter) wrestled with demons. And then it was upstairs to the top of the building where a black-box space has been turned into two performance spaces (with a fair amount of sound bleed between the two stages). In one room, the study, Cindy (Jennifer Ikeda) and Christina (Sarita Ocón) talk about French verbs, dreams and nightmarish doctors, and in another, the kitchen (an absolutely stunning design), Paula (Stacy Ross) chats with Sue (Leontyne Mbele-Mbong) before rekindling an old flame with the enigmatic Cecilia (Marga Gomez).

Some characters wander out of one short scene and into another, which is thrilling – like turning the play house into a playhouse, and we’re all kids having a blast playing pretend (but the conversations are decidedly not childlike). It’s that sense of discovery again – poking into corners of The Strand that audience members don’t usually see and, with all the fanciful design touches along our travel routes, feeling embraced by the idea of pretending to be in some other place in some other time with people who were imagined into being by a playwright with a lot to say. Kudos to MacKinnon and her team (notably Stage Manager Elisa Guthertz, whose team works with military precision and maximum affability) for such sterling execution of the Fefu challenge.

After intermission, audience members return to their seats in the theater for the final section of the play. We know these women better now, so the intricacies of the relationships, the shared histories and the personal traumas all carry more weight. The miracle of the actors is that they do feel connected by years of events, so their ability to shift from joy and frivolity to deep sadness and despair feels lived. There’s unevenness in the performances in some scenes, but that can’t obscure some stunning work by Castellanos as the gregarious but enigmatic Fefu, Goldfield as the effervescent Emma, Ross as the deceptively grounded Paula and Porter as the tormented Julia.

There’s no end to the discovery as Fornés allows us to spend 2 1/2 hours immersed in what women are thinking – a significant undertaking executed with a great deal of spirit and fun. In that sense, you can definitely say that hanging out with Fefu and Her Friends is a seriously good time.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

María Irene Fornés’ Fefu and Her Friends continues through May 1 at American Conservatory Theater’s Strand Theater, 1127 Market St., San Francisco. Tickets are $25-$110 (subject to change). Call 415-749-2228 or visit act-sf.org.