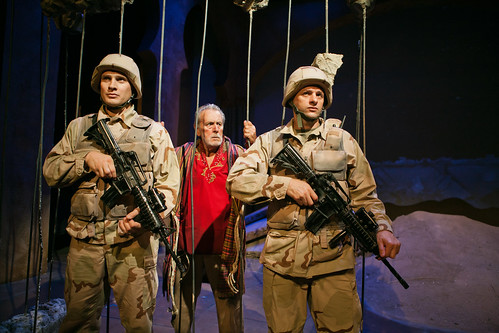

Rose (Caitlin Brooke) and Eddie (Jeffrey Brian Adams) attend a suspicious party in the musical Dogfight at San Francisco Playhouse. Below: Marines (from left, Nikita Burshteyn, Adams, Brandon Dahlquist, Andrew Humann, Aejay Mitchell and Andy Rotchadl) celebrate their leave atop the Golden Gate Bridge. Photos by Jessica Palopoli

There are two very good reasons to see the musical Dogfight at San Francisco Playhouse. The 2012 stage adaptation of the 1991 movie starring River Phoenix and Lili Taylor has its moments (mostly thanks to the emotional score by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul), but what really makes it connect are the lead performances by Jeffrey Brian Adams as a U.S. Marine with more depth under his gruff military exterior than even he may realize and Caitlin Brooke as a San Francisco waitress/folk singer who is smarter, stronger and more compassionate than anyone the Marine has ever known (or probably ever will know).

The premise of the show is a harsh one. A band of Marines lands in San Francisco the night before they ship out to Asia and, we can surmise, to the Vietnam conflict. It’s Nov. 21, 1963. No one knows President Kennedy will be assassinated the next day in Dallas, and on this night, the Marines engage in the age-old tradition of a “dogfight.” The Marine who parades the ugliest date across the dance floor at a dive bar wins the pot.<.p>

Private Eddie Birdlace (Adams) is especially gung-ho about the night’s event, as are his two buddies, whose names also start with B: Boland (Brandon Dahlquist) and Bernstein (Andrew Humann). The “three Bs” scour the streets of San Francisco for potentially prize-winning dogs (and also they wouldn’t mind getting laid), and Eddie wanders into a diner, where he hears Rose (Brooke) strumming a guitar and working on a song. There’s not really any universe in which Brooke could possibly be considered a “dog,” but costumer Tatjana Genser does her best to render the actor unattractive, especially in a yellow party dress she wears to accompany Eddie, after much persuasion, to the bar where she will unwittingly become a contestant in a hateful contest.

The songs in Act 1 include a rousing Marines on the town number, “Some Kinda Time,” which features the hyper-masculine choreography of Keith Pinto, a sleazy “let’s bag the dogs” number (“Hey Good Lookin'”) and a terrific ballad for Rose, “Nothing Short of Wonderful.” The one musical misstep here is the title song, sung by Rose and the winner of the dogfight, Marcy (Amy Lizardo). The song is strident and hard on the ears, which is the exact opposite of the rest of the score, which lives in the emotional strata where pop meets show tune – territory that feels reminiscent of Jason Robert Brown and Duncan Sheik.

One of the big challenges for book writer Peter Duchan is to make us care about Marines behaving badly. Sure, they’re shipping off to serve their country, but they are, in essence, assholes. We get to know Eddie best of all, and while he’s never quite likable, we at least begin to understand him, and the fact that he finally recognizes Rose for the wonderful person she is, definitely works in his favor. Eddie’s pals, on the other hand, are just crass stereotypes of soldiers gone wild, attempting to whore it up and ending up (secretly) in tears but still retaining bragging rights to protect the fragile (and enormous) male ego.

Act 2 has a harder time resolving the Eddie-Rose love story, shipping Eddie and friends off to the war and then flashing forward four years to 1967 when returning soldiers were spat on by hippies in the streets of San Francisco. The attempt to frame the story in a larger context ends up diminishing the central love story and providing a pat ending that feels tacked on rather than emotionally earned.

Director Bill English, who also designed the multi-level set dominated by a leaning tower of the Golden Gate Bridge, guides a strong cast through the two-plus-hour show, and musical director Ben Prince and his six-piece band help find all the emotion in the (mostly) rich Pasek-Paul score.

Dogfight isn’t a perfect musical, but its central love story, especially as brought to life by Adams and Brooke, who couldn’t be more emotionally grounded and powerful, has us sitting up and begging for more.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Dogfight continues through Nov. 7 at San Francisco Playhouse, 450 Post St., San Francisco. Tickets are $20-$120. Call 415-677-9596 or visit www.sfplayhouse.org.