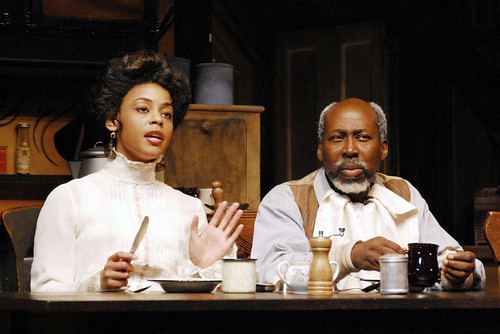

Denzel Washington is Troy Maxson and Viola Davis is his wife, Rose Maxson, in the screen adaptation of August Wilson’s Fences. The Paramount Pictures release, which Washington directs as well as stars in, opens Christmas Day everywhere. Below: Washington’s Troy walks home from work with Jim Bono, played by Stephen McKinley Henderson, a veteran of Wilson’s plays. Photos courtesy of Paramount Pictures

Denzel Washington is Troy Maxson and Viola Davis is his wife, Rose Maxson, in the screen adaptation of August Wilson’s Fences. The Paramount Pictures release, which Washington directs as well as stars in, opens Christmas Day everywhere. Below: Washington’s Troy walks home from work with Jim Bono, played by Stephen McKinley Henderson, a veteran of Wilson’s plays. Photos courtesy of Paramount Pictures

Hard to know which was more exciting: the art or the venue. Let’s go with both.

The Curran Theatre formally reopened Thursday, Dec. 15, after more than a year of renovations and refurbishments, and it’s gorgeous. In shades of elegance and Curran red, Carole Shorenstein Hays’ palace has once again cast open its doors.

The first official event, preceding the January bow of the Fun Home tour (get tickets now), was a homecoming of sorts. Thirty years ago, Hays launched August Wilson’s Fences, a play that would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize and sweep the 1987 Tony Awards. But before its Broadway glory, the play bowed at the Curran, and this week, the play returned in a manner of speaking. Denzel Washington directs and stars in the movie adaptation of the play, and the film had its San Francisco premiere at the Curran followed by a panel discussion with Washington, members of the cast (sadly, the busy Davis was absent due to work commitments) and Costanza Romero, a costume designer and Wilson’s widow.

There were more San Francisco roots in play: Washington spent some of his formative years nearly 40 years ago studying with the Curran’s neighbor, the American Conservatory Theater and worked across the street at the now-shuttered soup emporium, Salmagundi’s. After the movie screening and the panel discussion, Washington did something he said he’d always wanted to do but never imagined he could: he took a bow on the Curran stage.

It was a well-earned bow, certainly for Washington’s extraordinary body of work, his two Academy Awards and the stature he holds as one of the best of the best. But it’s also well earned for his achievement in Fences, a beautiful adaptation of the play that feels opened up (but not too much and not egregiously) and keeps the focus on the language and the performances, all of which are stellar. Music and underscore are used sparingly because, as Washington said, “the magic of August’s words, those are the notes. You don’t need an orchestra for Shakespeare. There’s Williams, Miller, O’Neill, Albee and Wilson. August’s work is rich, deep and wide.”

One reason the performances are so good may have to do with the fact that most of the cast (minus the younger actors who got too old) were in the 2010 Broadway revival that, once again, nabbed a passel of Tonys, this time for best revival and for its stars, Washington and Davis. Their chemistry and connection can be felt, even on screen, which is rare. And the supporting cast is just as good, especially Stephen McKinley Henderson, who plays best friend and fellow Pittsburgh garbage man to Washington’s Troy Maxson. Mykelti Williamson as Troy’s war-wounded brother Gabe does such finely tuned, extraordinary work it would seem his performance was always destined to be captured on screen. Russell Hornsby is Troy’s older son, Lyons, and Jovan Adepo makes a remarkable big-screen debut as Troy and Rose’s son, Cory.

Washington says he has fond memories of seeing the original Broadway production of Fences starring James Earl Jones, Mary Alice and Courtney B. Vance, so when producer Scott Rudin and Paramount Pictures approached him about seven years ago to talk about a movie, he was interested, but he wanted to do the play first. That’s how the revival was born. Now, six years later, Washington and his “core squad,” as Washington calls them, have returned. It’s rare for a movie adaptation to feature so many members of a stage company, but Washington says, “I remember when I was in A Soldier’s Play and when they made the movie, they used me and Adolph Caesar from the original cast but passed over another actor, Samuel L. Jackson. When it came time to make Fences, I thought, why should I go anywhere else? The band was tight. We had 114 some performances. It would be hard to get in the band.”

So, with his dream cast, Washington decided to film the movie in the actual location where it (and all of Wilson’s work) takes place: the Hill District in Pittsburgh. The choice lends even more richness to a film that is already dense with drama, remarkable language and performances that stun.

Washington says he felt Wilson, who died in 2005, on the set with him. There’s a scene toward the end of the film, when much of the cast is assembled, and a gate in the yard opens by itself. “That happened on its own,” Washington insists. “I knew August was with us and that we were all right.”

There will be more Wilson adaptations for the screen. The playwright’s epic 10-play cycle about African-American life in the 20th century, one play per decade (Fences is the ’50s), has been optioned by HBO with Washington producing. The idea is to do one play from the cycle each year for the next nine years. “We already have a script for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom [set in the 1920s and the only one of the plays not set in Pittsburgh].”

Before taking that bow onstage at the Curran, Washington added, “This work, these plays, these movies – this is what I was meant to be doing at this time in my life.”

Fences, rated PG-13, opens wide Dec. 25.

[bonus trailer]

But Seth’s primary test comes in the form of an intensely wound stranger who arrives with his 11-year-old daughter. Herald Loomis (Teagle F. Bougere in the role originated by director Lindo) is fresh from seven years hard labor on Joe Turner’s illegal chain gang, and he’s in search of the wife who abandoned him and his daughter, Zonia (Nia Reneé Warren, who shares the role with Inglish Amore Hills).

But Seth’s primary test comes in the form of an intensely wound stranger who arrives with his 11-year-old daughter. Herald Loomis (Teagle F. Bougere in the role originated by director Lindo) is fresh from seven years hard labor on Joe Turner’s illegal chain gang, and he’s in search of the wife who abandoned him and his daughter, Zonia (Nia Reneé Warren, who shares the role with Inglish Amore Hills).

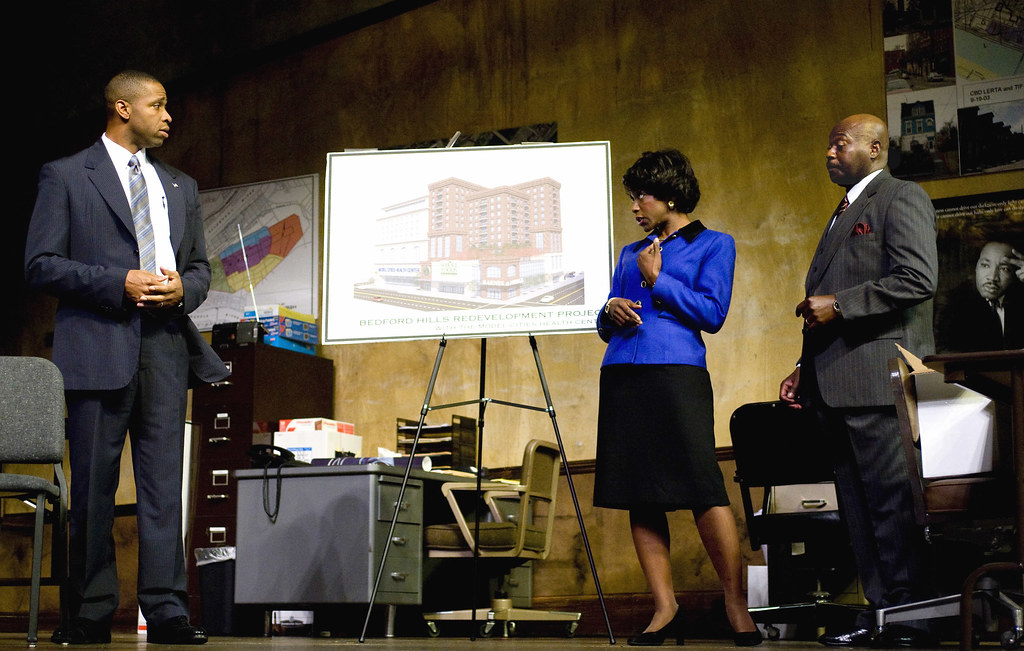

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

The project is spearheaded by old college chums Harmond Wilks (Aldo Billingslea, right), owner of a successful real estate agency, and Roosevelt Hicks (Anthony J. Haney), a banker. This redevelopment is just the beginning, especially for Harmond, who grew up in the Hill District and wants to take the energy of this project and turn it into a bid to become Pittsburgh’s first African-American mayor.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.

I first met him when I was in the second production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. As with many other academics, he was incredibly helpful and very, very accessible to me. The relationship was great. I remember one time when I was finishing a book about him, I wet to see King Hedley at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and we sat and talked for 3 ½ hours. He gave up his time to me, but I know many colleagues who had relationships like that with him. The last time I saw him was when he performed his solo piece, How I Learned What I Learned, in Seattle. He gave me a big hug. That’s the kind of person he was in my experience.

Even 3,000 miles away, San Francisco helps define New York.

Even 3,000 miles away, San Francisco helps define New York. We’ve seen San Francisco’s Best of Broadway announcing shows in recent weeks, then canceling them. The Wiz disappeared, then Whistle Down the Wind, then the new Irish musical Ha’penny Bridge.

We’ve seen San Francisco’s Best of Broadway announcing shows in recent weeks, then canceling them. The Wiz disappeared, then Whistle Down the Wind, then the new Irish musical Ha’penny Bridge.